This post is part of a series on the bog bodies displayed at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum at Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany. You can read the introductory post here.

A History of the Dätgen Man

In 1959, a headless body was discovered by peat cutters in a bog near Dätgen, a village in the district of Rendsburg-Eckernförde in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. The body was found with four wooden stakes [Gill-Robinson], which scholars have long speculated was indicative of a fear that the body would become a Wiedergänger, or an “again-walker,” a type of undead or restless spirit represented in Germanic folklore [Turner 1995]. The practice is staking bodies into the bog was not unusual [Abegg-Wigg 2022].

Six months later, in 1960, the head was recovered about 3 meters west of the original find with two additional stakes. Similar to the Osterby Head, the skull bore a Suebian knot hairstyle and had been flattened by the weight of the peat [Gill-Robinson].

As of 2014, tests had not conclusively proven that the head and body belong to the same person, and only the head had been carbon dated to 1760+B.P. It is unclear whether any tests have been conducted since 2014 to rectify this issue. The condition of the body is possibly too fragile for testing due to a conservation treatment of pentachlorophenol. Pentachlorophenol has long been used as a wood preservative. However, applying this treatment to the body “altered the original colour and texture of the skin and rendered the skin friable.” Pentachlorophenol is also toxic, requiring researchers to wear a respirator mask, nitrile gloves, and a full-length lab coat when working with the body [Gill-Frerking].

The Dätgen Man’s conservation also involved the use of thin copper wire to hold parts of the skeleton in place. This has unfortunately made it difficult to examine the fracture sites via radiography to determine whether the extensive injuries were inflicted peri- or postmortem. Several ribs were removed at some point during the preparation of the body [Gill-Frerking].

Many of the articles relevant to the Dätgen Man do not appear to have been digitized; I am discovering that this is a pattern with older German bog body scholarship, for whatever reason. This article will be expanded accordingly when more scholarship is accessible.

The Present Display

The Dätgen Man is displayed separate from the Moorleichen exhibit in an exhibit titled Tod und Jenseits (“Death and Beyond”). The video above features a brief walkthrough of the exhibit, ending with a shot of the Dätgen Man’s body.

Tod und Jenseits focuses on pre-Christian interpretations of death and the afterlife. The lighting is extremely dark, though this is presumably a stylistic decision and not done out of concern for the artifacts; the artifacts themselves are lit and the Moorleichen exhibit is not nearly as dark as Tod und Jenseits.

A small collection of relevant archeological finds are presented alongside a reconstruction of a funeral pyre. Artifacts presented include the dramatic Braak Bog Figures found in a bog in Schleswig-Holstein (conservation of these figures was performed by Karl Schlabow, whose methods have been deemed aggressive; he also worked on the Osterby Head, presumably adding the unoriginal lower mandible) and grave finds from Hüsby.

The headless body found at Dätgen is displayed in an otherwise empty offshoot attached to the main room of the exhibit. It is the only display housed in this part of the room. The case is lit from within. The body is viewable from the top down lying on a bed of peat. The walls of the case are otherwise painted black. The head that has been generally assumed to belong to the Dätgen Man was not displayed alongside the body at the time of my visit (September of 2023).

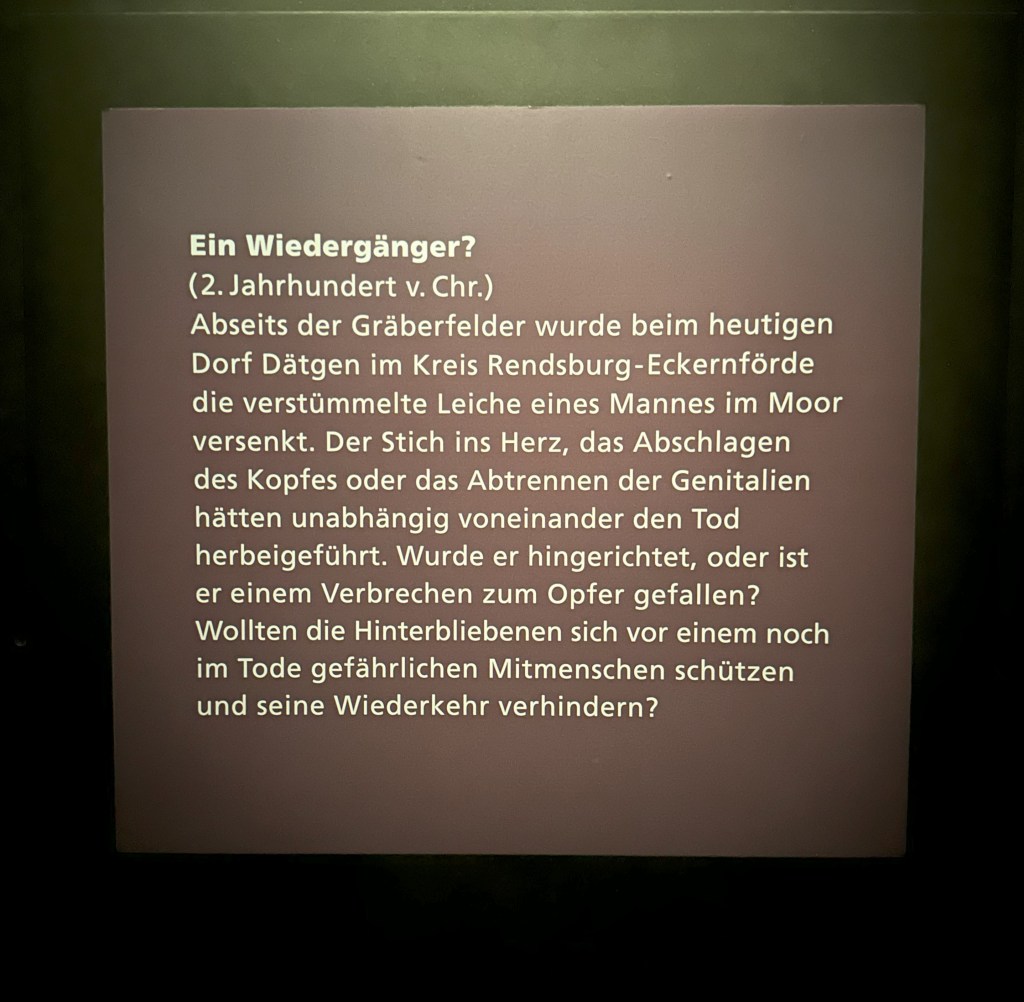

A label on the otherwise blank wall adjacent to the case does not explicitly identify body as “The Dätgen Man,” though it does place his discovery near the village of Dätgen. Instead, it focuses on the possibility that the body was staked to the bog due to the fear that he might become a Wiedergänger, tying the body in thematically with the rest of the Tod und Jenseit exhibit.

The label notes that he was stabbed through the heart and that his head and genitals were removed. The recovery of the head is not mentioned. Given the uncertainty surrounding the connection between the head and body, this seems like a wise decision. I am, however, a little uncertain on where the head is located at present. Sources online claim it is (or was) on display at Schloss Gottorf, but if it was featured anywhere in the Moorleichen or Tod und Jenseit exhibits, I must have somehow overlooked it.

Leave a reply to Bog Bodies at Schloss Gottorf: An Introduction – The Bog Body Resource Cancel reply