As fond as I am of bog bodies in general, I have something as a soft spot for the Tollund Man. Perhaps it’s that his expression is one of the most peaceful, so well-preserved that he almost appears to be sleeping. Perhaps it’s the role that Danish bog bodies (and Danish archeologist P.V. Glob) played in establishing a precedent for their preservation and display in museums. Or perhaps it’s simply that the Tollund Man was the very first bog body I learned about—thanks not to a museum visit, but rather thanks to a poem.

On the surface, I suppose it’s fairly typical to say that my undergrad capstone led me to my thesis topic. But it was not, in my case, a smooth transition. My bachelor’s degree is in English literature and my capstone focused on Beowulf. I was working with both the original Old English text and various translations, which introduced me to Irish poet Seamus Heaney (whose translation of Beowulf is considered one of the more readable, though not the most accurate). Among his beloved work is a poem called “The Tollund Man.”

A few years later, when I started working on this project, I felt strongly that I would need to visit Denmark to see some of the most famous bog bodies in person, Tollund Man included. I was lucky enough to receive departmental funding (my most heartfelt thanks to the Nguyen family) that made the trip possible. I promptly reached out to Ole Nielsen, the director of the Silkeborg Museum where Tollund Man has long been displayed, to arrange a meeting.

I was lucky enough to visit the Silkeborg Museum on a day when it wasn’t open to the public, which allowed plenty of time for conversations and photographs uninterrupted. Nielsen greeted me at the door and invited me to his office, where we talked for an hour over coffee before heading through the back to a separate building, which is almost entirely dedicated to the Tollund Man and bog-related finds.

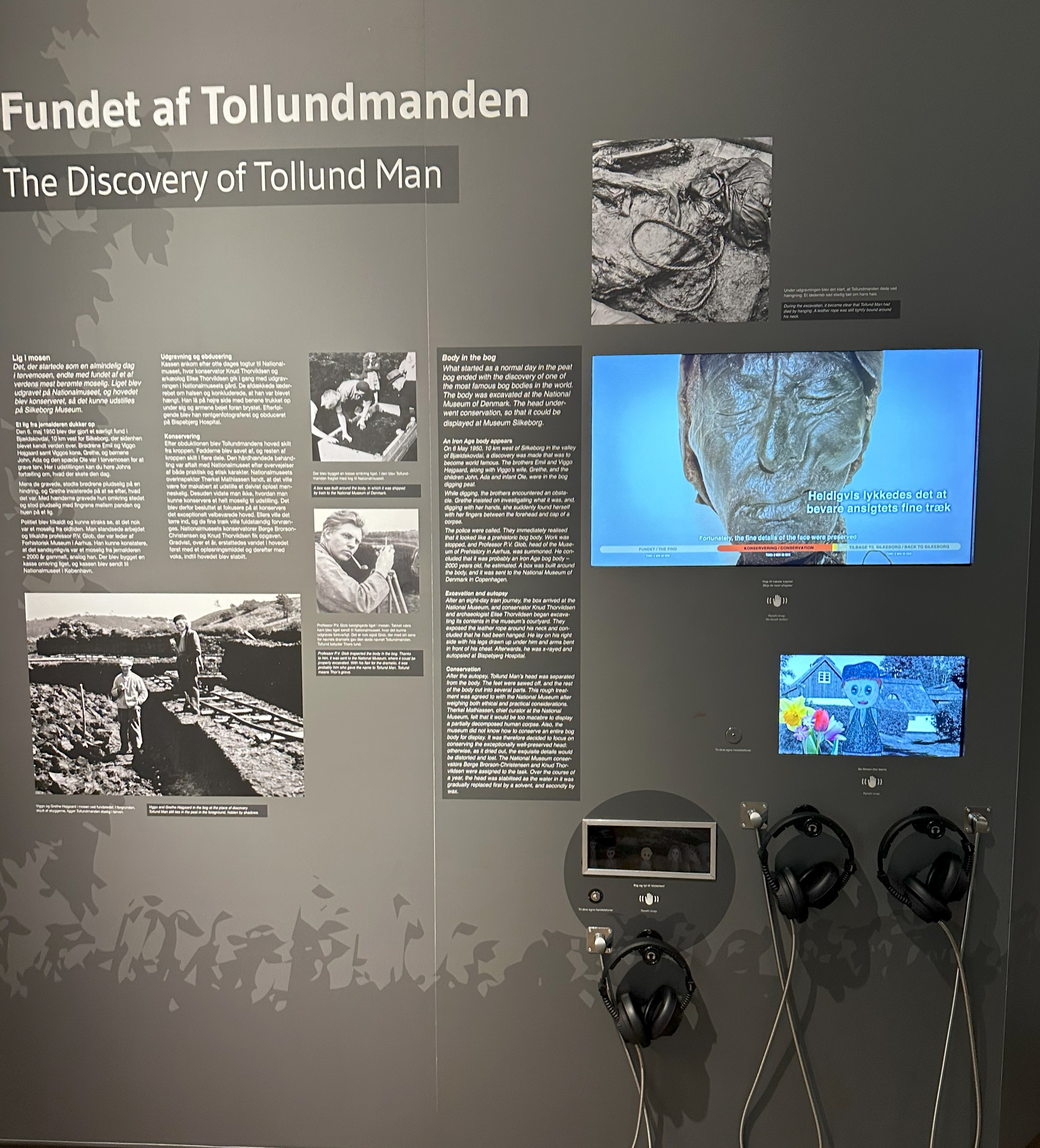

Discovery & Preservation

During our conversation, Nielsen was kind enough to walk me through the history of the Tollund Man from discovery to present. Much of this information was also included in his display.

Tollund Man was discovered in Bjældskovdal peat bog near Silkeborg on 8 May 1950 by peat cutters Viggo and Emil Hojgaard. He was not excavated on location, but rather a block of peat containing him was removed from the bog and transported to a different location to allow for excavation under more controlled conditions. Almost immediately afterward, the remains were taken to Bispebjerg Hospital in Copenhagen where an autopsy was performed. This was conducted, presumably, much as an autopsy of a more recent murder victim would be performed. It was established that his internal organs were all present—flattened, but identifiable.

In his digestive tract they found about a quarter of a liter of food, estimated to have been eaten around 12-24 hours before his death. The most current research indicates that this meal likely comprised a porridge of barley, flax, seed, and fish [Nielsen 2021].

There was some hesitation about displaying the Tollund Man at the Silkeborg Museum, initially. This seems on the surface to parallel other debates over whether discoveries should go to state vs. local museums (e.g., movements in England that called for the Lindow Man to be returned to Cheshire rather than displayed in the British Museum), but Nielsen explained that there was in fact little interest on the national level in displaying human remains at the time, with greater emphasis placed on artifacts. In short, there was some question as to whether the Tollund Man would be displayed at all, as this was relatively new ground being tread. Because there were fewer methods available at the time to understand these remains (DNA testing, stable isotope analysis, etc.), researchers at the time did not know what value preserving these remains would hold in the future.

There were, of course, also ethical concerns—was it right to display a human body in a museum? It wasn’t until the Grauballe Man was discovered two years later that archeologist P.V. Glob made the revolutionary decision to advocate for his display in a museum. Glob was also integral in the decision not to excavate the Tollund Man on-site, but rather to transport his remains to another location first.

The method used to preserve Tollund Man had previously been used to preserve fish and tissue for microscopy. This method involves the gradual replacement of water with wax. The head was placed in de-mineralized water to dilute and remove the impurities from the bog water. From there, they added alcohol in increments until eventually the water was replaced with alcohol entirely. The process was then repeated with liquid wax. Afterward, the head was cooled, stabilizing the wax. This process did not merely encase the remains in wax but rather infused them with it, preventing the remains from collapsing on a cellular level.

Compared to the tanning process used to preserve the Grauballe Man, it would appear that this method was more successful in preserving the facial features. though this can also be attributed in part to the exceptional preservation of the Tollund Man’s skull by the bog itself. It is not uncommon for bones to deteriorate or soften under these conditions, resulting in features being crushed beneath the weight of the peat.

The decision was made to preserve only Tollund Man’s head for display. The reasoning behind this is somewhat unclear. It might’ve been due to concerns about the ability to preserve something of this size, given the wax method had only been used on fish and tissue samples before. It might also have felt, in a roundabout way, less shocking to display only a head as opposed to full human remains. Other body parts were preserved for research purposes using alternate methods, but most have not been placed on display.

The Current Exhibit

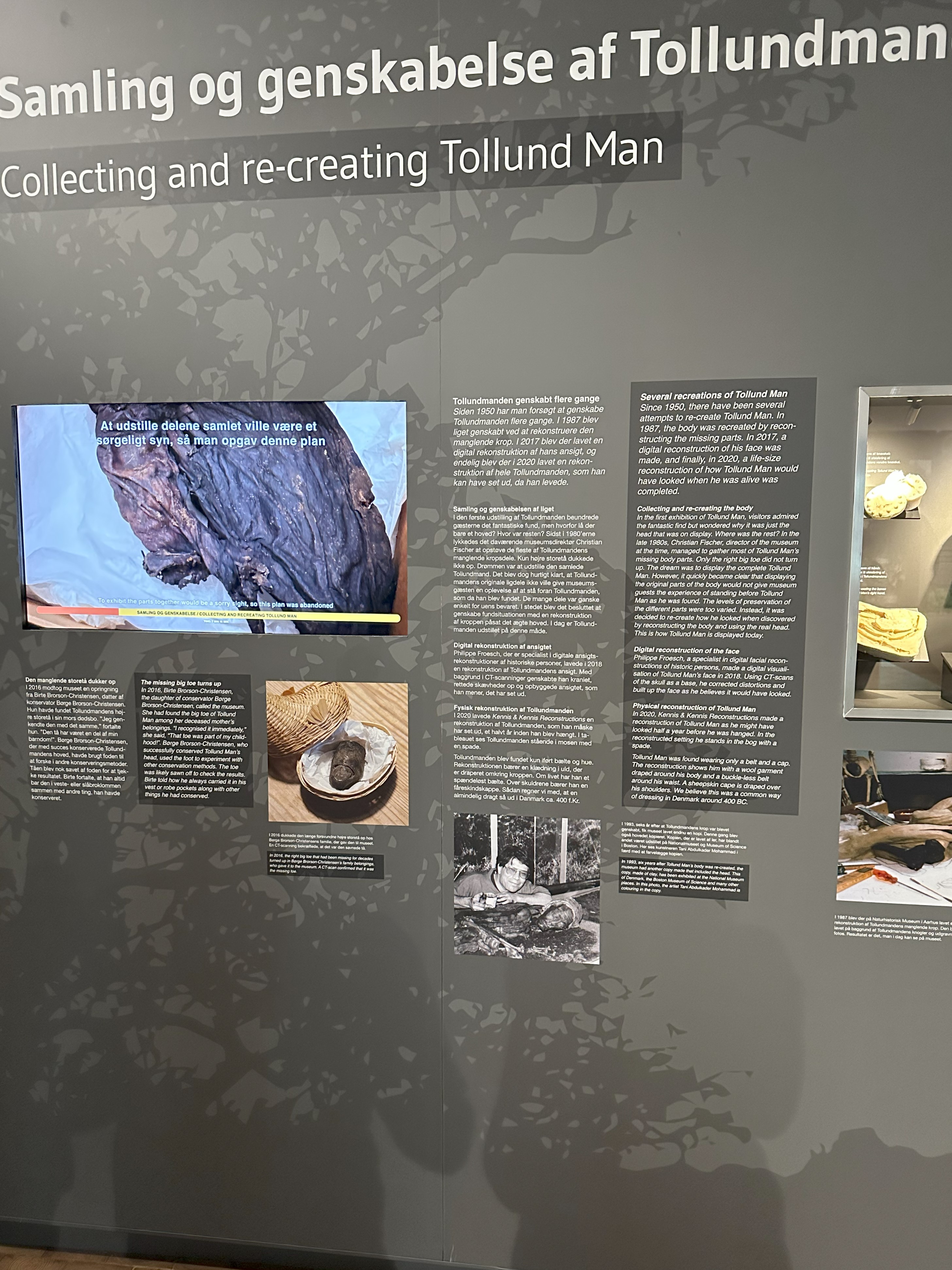

Upon entering the exhibit, visitors are greeted by a reconstruction of the Tollund Man, staged at the center of the room. This reconstruction is the work of Netherlands-based company Kennis & Kennis, who used a 3D scanning and printing to bring the Tollund Man to life.

The effectiveness of facial reconstructions in museum exhibits has on occasion been called into question. Bog bodies are uniquely positioned in that reconstructive artists have more forensic information available to them than, say, if they were working with entirely skeletonized remains. [Wilkinson] In the case of the Tollund Man, it is undoubtedly an accurate reconstructions—any visitor who questions this need only walk a few rooms over and compare the reconstruction against his actual remains.

This, in turn, begs the question: how informative is a reconstruction when much of the same information can be garnered from the remains themselves? More often than not, reconstructions exist to help us humanize the dead, bridging the cognitive gap between a fragmented skull behind a pane of glass and a human life. Bog bodies as well-preserved as Tollund Man are already more than capable of conveying their own humanity—it is for this reason that they have long captured the public imagination.

In the case of the Silkeborg Museum’s reconstruction, they obviously have both the financial means and space to accommodate the reconstruction, so this is by no means a criticism of their display. I simply wanted to take this opportunity to address the necessity of reconstructions in designing bog body exhibits. Many spaces choose to prioritize contextual information and artifacts over reconstructions—for example, the British Museum previously commissioned a facial reconstruction of the Lindow Man, but it was eventually removed from display. Although I have previously criticized the British Museum for its design choices, I believe the decision not to include the facial reconstruction in the current display was the right one, given the already limited space the display designers were working with.

But I digress. The room surrounding the reconstruction is chock-full of information and media that contextualizes the Tollund Man’s discovery, preservation, and subsequent reactions to him over the years. As mentioned in the section above, when the Tollund Man was first discovered, the decision was made to only preserve his head for display. Display cases around this entry room explain this decision in more detail; they also feature body parts that were separately preserved for various reasons, including the right foot and a toe that was taken by a researcher and kept for years (a good luck charm or a keepsake?) before being returned to the museum in 2016.

Text is in both Danish and English. The director himself pointed out the reliance in some places on large paragraphs of text, but this is supplemented by an array of other media, including video and audio components.

East of this first room is a hall which houses the Elling Woman and other bog-related finds. This took me somewhat by surprise, as the Elling Woman is herself a bog body and I had expected her to be treated with similar reverence to the Tollund Man; the director informed me that, given the funding, the museum would choose to upgrade her display, but it sounds as though this is not feasible at present.

Like the Osterby Head displayed at Schloss Gottorf, the Elling Woman is perhaps most noteworthy among bog bodies for the preservation of her distinctive hairstyle. She is otherwise not so well-preserved as the Tollund Man; her face and organs had all deteriorated by the time she was discovered [Gill-Robinson]. She is displayed wrapped in her sheepskin cape and leather cloak on a bed of stepped peat. Beside her, a number of mannequin heads demonstrate how her hairstyle (sometimes called an “Elling Braid”) was achieved.

Other artifacts on display in this hall include bronze neck rings, wooden effigies, and human bones. This room felt a little less interactive than the entrance hall, and there was significantly less context provided for the Elling Woman compared to the Tollund Man. It felt as though this room was dedicated more to explaining the cultural significance of bogs among Bronze and Iron Age peoples as opposed to highlighting any one discovery.

Which leads us to the third and final room. The only object on display in this room is the Tollund Man himself; with the exception of one wall of text, the exhibit relies on the previous rooms to contextualize the Tollund Man for the visitor. The lights in this room are on a motion sensor, meaning the display is kept entirely dark unless someone is visiting [“Seværdighed i Silkeborg”]. Considering other bog bodies like the Lindow Man have suffered light damage due to excess exposure, this seems a sensible precaution [Bradley 2008].

The preserved head is displayed with a reconstructed body, almost identical to early photographs from around the time of his excavation. The case is lit from within, a design choice which prevents the glare/reflection that is so often disruptive in viewing dimly lit displays. Additionally, stools are available for those who wish to sit and contemplate the Tollund Man, and there are handrails surrounding his case, presumably to assist anyone who wishes to lower themselves to get a closer look at his face.

Director Ole Nielsen was also kind enough to let me have a look at the climate controls for the Tollund Man’s case, a system which involves temperature controls and a small tank of distilled water to control humidity levels.

This is a museum that was able to dedicate time, resources, and space to thoroughly contextualizing the bog bodies in its care. Unlike larger museums like the British Museum and the Moesgaard, who are responsible for a wide array of artifacts in addition to any bog bodies in their collections, the Silkeborg has unquestionably presented the Tollund Man as their star attraction.

The Poem

Appropriately, an excerpt of the Seamus Heaney poem is featured in the Silkeborg Museum’s display, written into the guest book by Heaney himself when he visited in 1973:

from The Tollund Man

Bridegroom to the goddess

She tightened her torc on him

And opened her fen,

Those dark juices working

Him to a saint’s kept body . . .

Seamus Heaney, 16th October 1973

Leave a reply to Bog Bodies at Schloss Gottorf: The Rendswühren Man – Bog Body Database Cancel reply