-

The Dätgen Man and Iron Age Sacrificial Sites

This post is part of a series on the bog bodies displayed at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum at Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany. You can read the introductory post here.

A History of the Dätgen Man

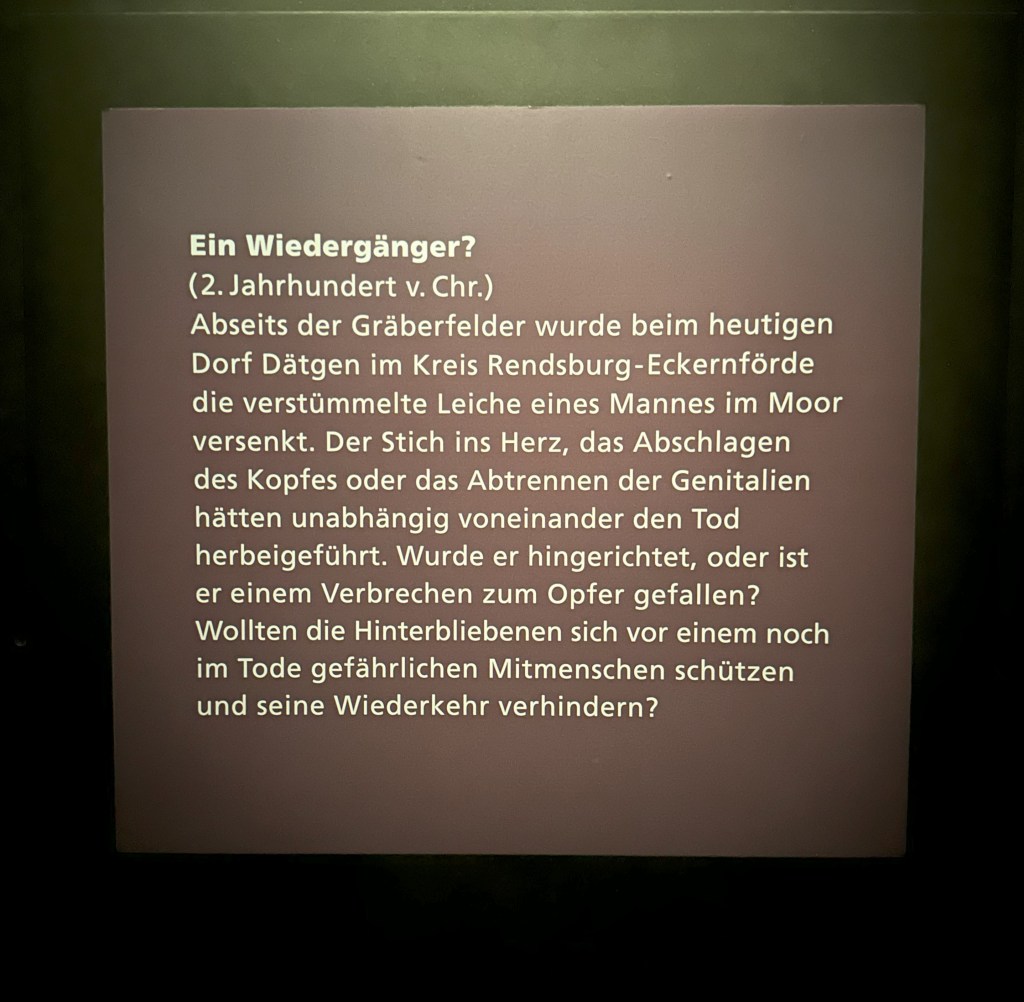

In 1959, a headless body was discovered by peat cutters in a bog near Dätgen, a village in the district of Rendsburg-Eckernförde in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. The body was found with four wooden stakes [Gill-Robinson], which scholars have long speculated was indicative of a fear that the body would become a Wiedergänger, or an “again-walker,” a type of undead or restless spirit represented in Germanic folklore [Turner 1995]. The practice is staking bodies into the bog was not unusual [Abegg-Wigg 2022].

Six months later, in 1960, the head was recovered about 3 meters west of the original find with two additional stakes. Similar to the Osterby Head, the skull bore a Suebian knot hairstyle and had been flattened by the weight of the peat [Gill-Robinson].

As of 2014, tests had not conclusively proven that the head and body belong to the same person, and only the head had been carbon dated to 1760+B.P. It is unclear whether any tests have been conducted since 2014 to rectify this issue. The condition of the body is possibly too fragile for testing due to a conservation treatment of pentachlorophenol. Pentachlorophenol has long been used as a wood preservative. However, applying this treatment to the body “altered the original colour and texture of the skin and rendered the skin friable.” Pentachlorophenol is also toxic, requiring researchers to wear a respirator mask, nitrile gloves, and a full-length lab coat when working with the body [Gill-Frerking].

The Dätgen Man’s conservation also involved the use of thin copper wire to hold parts of the skeleton in place. This has unfortunately made it difficult to examine the fracture sites via radiography to determine whether the extensive injuries were inflicted peri- or postmortem. Several ribs were removed at some point during the preparation of the body [Gill-Frerking].

Many of the articles relevant to the Dätgen Man do not appear to have been digitized; I am discovering that this is a pattern with older German bog body scholarship, for whatever reason. This article will be expanded accordingly when more scholarship is accessible.

The Present Display

The Dätgen Man is displayed separate from the Moorleichen exhibit in an exhibit titled Tod und Jenseits (“Death and Beyond”). The video above features a brief walkthrough of the exhibit, ending with a shot of the Dätgen Man’s body.

Tod und Jenseits focuses on pre-Christian interpretations of death and the afterlife. The lighting is extremely dark, though this is presumably a stylistic decision and not done out of concern for the artifacts; the artifacts themselves are lit and the Moorleichen exhibit is not nearly as dark as Tod und Jenseits.

A small collection of relevant archeological finds are presented alongside a reconstruction of a funeral pyre. Artifacts presented include the dramatic Braak Bog Figures found in a bog in Schleswig-Holstein (conservation of these figures was performed by Karl Schlabow, whose methods have been deemed aggressive; he also worked on the Osterby Head, presumably adding the unoriginal lower mandible) and grave finds from Hüsby.

The headless body found at Dätgen is displayed in an otherwise empty offshoot attached to the main room of the exhibit. It is the only display housed in this part of the room. The case is lit from within. The body is viewable from the top down lying on a bed of peat. The walls of the case are otherwise painted black. The head that has been generally assumed to belong to the Dätgen Man was not displayed alongside the body at the time of my visit (September of 2023).

A label on the otherwise blank wall adjacent to the case does not explicitly identify body as “The Dätgen Man,” though it does place his discovery near the village of Dätgen. Instead, it focuses on the possibility that the body was staked to the bog due to the fear that he might become a Wiedergänger, tying the body in thematically with the rest of the Tod und Jenseit exhibit.

The label notes that he was stabbed through the heart and that his head and genitals were removed. The recovery of the head is not mentioned. Given the uncertainty surrounding the connection between the head and body, this seems like a wise decision. I am, however, a little uncertain on where the head is located at present. Sources online claim it is (or was) on display at Schloss Gottorf, but if it was featured anywhere in the Moorleichen or Tod und Jenseit exhibits, I must have somehow overlooked it.

case study, Daetgen Man, Dätgen Body, Dätgen Head, Dätgen Man, decapitated, display, folklore, German bog bodies, germany, gottorf, gottorf castle, gottorp, photo, pre-1950s, preservation, schleswig, schloss gottorf, state archeology museum, state museum of archeology, Suebian knot, text, Wiedergänger -

The Rendswühren Man

This post is part of a series on the bog bodies displayed at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum at Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany. You can read the introductory post here.

A History of the Rendswühren Man

Found in June 1871, the Rendswühren Man marks the oldest date of discovery among the bog bodies in Schloss Gottorf’s collection. P.V. Glob puts the location of his discovery at Rendswühren Fen near Kiel, Germany, though some online sources alternatively refer to this location as “Heidmoor.” According to an article by Angelika Abegg-Wigg (the current curator of Iron Age artifacts at Schloss Gottorf) and Ben Krause-Kyora, the bog in question is additionally sometimes referred to as “Großes Moor”—literally “Big Bog” [Abegg-Wigg 2016]. They place the bog between Neumünster und Bornhöved, south of B430.

The name(s) of whoever discovered the Rendswühren Man (presumably, a peat cutter or cutters) seem to be lost to history. The discovery was investigated by Johanna Mestorf, a self-taught archeologist who is often credited as Germany’s first female professor and who was working as curator of the Kiel Museum at the time.

The exact position of the body at the time of discovery is well-documented: the Rendswühren Man lay face down in the bog at a slight incline with his right foot crossed over his left [Gill-Robinson, who wrote additional articles under the name Gill-Frerking; sources are cited based on the name they were published under], and was naked except for the left leg, which was covered by a piece of leather with the pelt facing inward, and bound by a sort of leather garter. His head was covered in a large rectangular woollen cloth and a cape made of pieces of skin sewn together, with a hole in the forehead, possibly indicating he was struck in the head after being covered [Glob; Abegg-Wigg 2016]. Glob’s wording is somewhat vague, but Abegg-Wigg and Krause-Kyora variously describe the materials used as twill wool (“geköpertem Wollstoff”), sheepskin (“Schaffell”) and leather with hair (“behaartem Leder”). Additionally, a vest and tunic were found near the body [Gill-Robinson]. Early attempts to date the body were based on these articles of clothing, estimated to have been from around 100-200 CE. Over a century later, 14C-AMS dating would agree with this assessment [van der Plicht].

Much of this clothing has deteriorated or been lost. This is due in part to the body being displayed on a farm cart in a nearby barn shortly after its discovery [Glob]. The find was reported in a local newspaper, drawing visitors who took scraps of fabric and other keepsakes before the body was transported to Kiel.

An 1871 journal publication, re-discovered by Heather Gill-Robinson while searching archival materials, documents the discovery, excavation, and examination of the body. Physical examination and autopsy was conducted by a Dr. Hansen and Dr. Kaestner. The skin was described as dark black-brown and parchment-like prior to post-excavation conservation treatments. During the excavation process, the mandible was detached from the skull. The left metatarsals and phalanges were absent, possibly due to damage by the peat spade. The brain was reportedly preserved as a sample for an anatomical museum, but its ultimate fate is unknown [Gill-Robinson].

The body was preserved via smoking in an oven, though records on the specifics of this treatment are limited. Digital radiographs taken of the Rendswühren Man’s head revealed that the skull is missing, having been reconstructed using “wire and several unknown materials.” Gill-Frerking speculates that modeling clay or similar might’ve been used to provide facial structure. Metal rods inserted into the neck seem to have given it an unnaturally elongated appearance [Gill-Robinson; Gill-Frerking]. Another unknown material was used to replicate teeth. The reliance on metal interfered with imaging, and the absence of the skull has made it impossible to compare modern findings against the 19th-century autopsy report [Gill-Frerking].

What’s interesting about the Rendswühren Man is that he was preserved at all—a large number of bog bodies found throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were either reburied or allowed to decay [Joy 2014]. Prior to the Grauballe Man’s discovery in 1952, it was still widely considered unethical to display human remains in a museum [“Displaying a Bog Body”]. Yet Johanna Mestorf and others made the decision to preserve the Rendswühren Man all the way back in 1871. He was left out on a cart for visitors to view—to his detriment, yes, but this nevertheless demonstrates that not everyone had qualms about viewing human remains.

The Present Display

The Rendswühren Man is displayed in a semi-dark room as part of the Moorleichen exhibit at Schloss Gottorf, which is contextualized by various Iron Age artifacts. I have mentioned in previous articles that I am not overly fond of the decision to display bog bodies alongside unrelated Iron Age artifacts—while it places them in the broader context of their era, I’ve found exhibits focused on the cultural significance of bogs and bog-related finds to be more thematically cohesive and engaging.

The State Museum of Archeology is housed in a historic castle, the ongoing preservation of which no doubt presents some limitations as far as space, architecture, and alterations. However, the castle houses a separate exhibit—which I hope to address in a future article—that is more focused on the sacrificial significance of bogs. At present, I am not totally clear on why these two exhibits are separated.

Like the other bog bodies featured in the Moorleichen exhibit, the Rendswühren Man is displayed in an enclosed case with only one glass side for viewing. The backdrop features a sepia interpretation of a shrubby bog and he is presented on a bed of dried turf, lying face up rather than face down as he was discovered. While generally appreciating displays that make an effort to show the body in the context of its discovery, I do think that presenting the Rendswühren Man face up is the logical choice. A rough orange-brown cloth (not believed to be historical in origin) is draped across his pelvis. He was previously displayed without a cloth covering his genitalia; presumably this was changed with the variable sensitivities of museum-goers in mind.

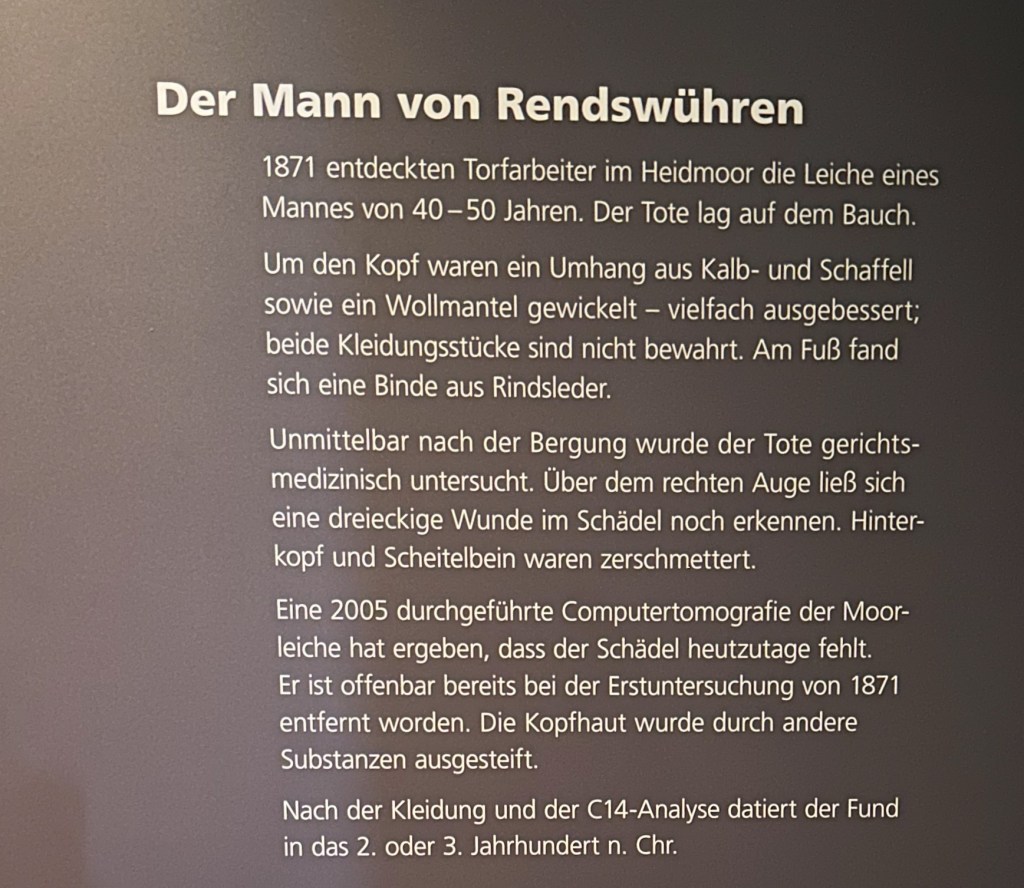

The label for the Rendswühren Man (or “Der Mann von Rendswühren”) describes him as having been approximately 40-50 years of age at the time of death. The cloaks are here described as being made of calfskin and sheepskin (“Kalb- und Schaffell”) as well as wool (“Wollmantel”), with a bandage of cowhide (“Rinsleder”) around the foot.

The label describes an autopsy having been performed on the Rendswühren Man shortly after his discovery; the triangular wound to the skull, also described by Glob, was observed. The back of the skull and parietal bone were also shattered. A tomographic scan conducted in 2005 revealed that the skull was not present, indicating that it was likely removed during the initial autopsy (described in greater detail in the section above; this is the only context the placard provides).

I found it interesting—and a little frustrating—that the Moorleichen exhibit does not seem to mention Johanna Mestorf. The NOVA website cites her as having coined the term “Moorleichen,” and the decision to smoke the body for preservation was undoubtedly revolutionary at the time. Is it necessary to mention relevant archeologists in a museum exhibit, which should perhaps be focused on the finds themselves? I’m not sure where I stand on this. Danish bog body exhibits like that at the Silkeborg Museum certainly do not hesitate to credit P.V. Glob for his contributions to the field, so it feels like the Rendswühren Man’s display is missing context by comparison.

-

The Osterby Head

This post is part of a series on the bog bodies displayed at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum at Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany. You can read the introductory post here.

History of the Osterby Head

In May of 1948, a peat cutter named Max Müller working in Köhlmoor near Osterby unearthed a human head wrapped in a cape of roe deerskin [Kersten; Glob]. I am hesitant to include the precise date of this discovery as sources seem to contradict one another: P.V. Glob puts it at the 28th while Heather Gill-Robinson and Karl Kersten put it at the 26th. The exhibit at Schloss Gottorf lists only the year of discovery.

The location of Köhlmoor is put at 54°26′51″N 09°46′09″E by Kersten, which aligns with Glob and other researchers placing Köhlmoor as lying “south-east of Osterby.” If this precise placement is accurate, then it would appear that Köhlmoor was, like many northern European bogs, drained and repurposed as farmland. Some scholars tend to drop the umlaut from Köhlmoor in favor of “Kohlmoor,” likely for convenience. “Köhl” is Low German (a dialect native to Schleswig-Holstein) for “cool” or “cold,” whereas “Kohl” is standard German for cabbage.

Following the discovery, the skull was taken to the home of Otto, reportedly Max Müller’s brother. The Schleswig-Holstein Museum Vorgeschichtliche Alterttime (Schleswig-Holstein Museum of Prehistoric Antiquity, now defunct) was notified of the discovery and additional pieces of skull and brain were recovered from the discovery site [Kersten]. The skull was examined by Hans Weinart at the University of Kiel. It was estimated that the Osterby Man was around 50-60 years at the time of his death. The skull had been crushed by the weight of the peat and the first two vertebrae were found separated. Methods used to determine the age and sex of the specimen are not detailed in older documents, but the sex was later ascertained via morphological assessment of the supraorbital margin, glabella prominence, orbits, and mandibular condyle [Gill-Robinson].

Efforts were made to locate the rest of the body with no success; this has led some to believe that the head was buried on its own. However, in the case of other decapitated bog bodies like the Dätgen Man, the body and head were found some distance from one another [van der Sanden]. This would indicate that it is possible the body of Osterby Head was at some point present in the bog at a different location. At the least, it is clear that the head was separated from the body before burial by a sharp implement, which severed the second cervical vertebra [Kersten; Glob]. Forensic evidence suggests that the Osterby Man was killed by a blow with a blunt object to the left temple [Glob; van der Sanden]. The Osterby Head is an example of an instance where flesh was poorly preserved, not due to any action taken after its exhumation, but rather due to the conditions of the burial or location within the bog itself—only the bone, scalp, and hair survived.

The Osterby Head’s distinctive knotted hairstyle is described in Tacitus’ Germania as popular among the Suebi tribe, though whether this would indicate that the Osterby Man was Suebian in origin is unclear—the hairstyle was supposedly adopted by a small number of men from other tribes [Tacitus]. Interestingly, the Dätgen Man—who was also beheaded before burial—exhibits a similar hairstyle, though his Suebian knot is bound at the back of the head rather than the side.

The head has been dated using 14C-AMS, or accelerator mass spectrometry, which is a carbon dating method. The results of this testing dated the hair sample to 1895+30 BP, which corresponds to the estimated date of CE 75-130 [van der Plicht; Gill-Robinson]. However, given that the hair sample was taken from the private collection of Alfred Dieck—a controversial German archeologist whose work on bog bodies has proven faulty—there is a possibility that the hair was not actually from the Osterby Head.

The skull was reconstructed post-excavation by Karl Schlabow. The heavy-handedness of this reconstruction poses various problems for modern researchers. It is unknown whether the present construction is accurate to the original shape, which renders osteometric and forensic analysis unreliable. Multi-slice Computed Tomography (MSCT) carried out in 2005 revealed that the cranium was filled with plaster during reconstruction, which interferes with imaging. Additionally, Gill-Robinson concluded upon close examination that the mandible was taken from another specimen during the reconstruction process; photographs of the initial find do not indicate that the original mandible was present, and the origin of the current mandible remains unknown [Gill-Robinson].

Some unverified online sources indicate that the Osterby Head was stabilized for display by filling with gypsum, or calcium sulfate dihydrate, which is sometimes used in bone grafting and repair. I am yet to find a source to confirm this.

Current Display

The Osterby Head is displayed in a semi-dark room as part of the Moorleichen exhibit at Schloss Gottorf alongside several other bog bodies and an array of Iron Age artifacts. This decision to display the bodies alongside other Iron Age finds resembles the Lindow Man’s display in the British Museum; however, the Moorleichen exhibit at Schloss Gottorf plainly dedicates more space and resources to the bodies themselves. A label to the left of the display gives a short summary of some of the history detailed above. A placard to the right demonstrates how the Osterby Head’s hairstyle was achieved and features an image of Trajan’s Column believed to depict a Suebian knot. It also includes a brief excerpt from Tacitus regarding the hairstyle.

The Osterby Head’s display is interesting in that only a head is exhibited, which calls for a different design. This was originally the case for the Tollund Man, although the circumstances were different (the Tollund Man was discovered with his body in-tact and was not decapitated; the decision was made to preserve only his head for display, perhaps because researchers were not confident at the time that they could preserve his entire body). The Osterby Head’s current display can be compared against a recreation of the Tollund Man’s previous display below.

The difference in the presentation of these remains is likely due in part to when they were designed. It is also possible that the different levels of preservation resulted in different considerations. Unlike the Tollund Man’s old display, which featured his head lying on its side (likely mimicking the position in which he was discovered) along with the belt and garrote he was found with, the Osterby Head is suspended in its case so that it almost appears to be floating. The case is enclosed on all but one side, likely to minimize light exposure. There is no peat included in the case—a common feature in other displays—and the head is not displayed with the deerskin wrap it was found in, nor any sort of representation or reconstruction of it.

It is unclear whether the deerskin wrap survived beyond the 1948 discovery. Contemporary sources provide details on the dimensions and construction of the garment, but I have been unable to locate more recent analysis, perhaps indicating that the wrap has since deteriorated.

A video of the Osterby Head on display can be viewed below:

The small, enclosed case had the unexpected effect of feeling almost claustrophobic. This is not exclusive to the Osterby Head; all the bog bodies in Schloss Gottorf’s collection feature this one-sided viewing design, which, compared to displays like the Grauballe Man at the Moesgaard Museum—which features a unique glass top, allowing the body to be viewed from the floor above as one of five possible angles—feels limiting. Of course, the Moorleichen exhibit being housed in a historic castle is likely a factor in some design limitations, so the comparison to the more modern Moesgaard Museum is perhaps irrelevant.

Overall, the Osterby Head’s display is functional; I appreciate that is is given a position of importance in the Moorleichen exhibit and that the placards provide context for both the history of the discovery and the skull’s hairstyle. Questions remain about initial and ongoing preservation efforts as well as the fate of the deerskin wrap.

-

Bog Bodies at Schloss Gottorf: An Introduction

It could easily be argued that bog bodies tend to capture the public imagination due to the exceptional preservation of their skin; the face of the Tollund Man, for example, is significantly less alarming to look at than even some other types of mummified remains, making him an ideal candidate for display in a museum. This is not the case for all bog bodies, which exist on a spectrum that ranges from well-preserved enough to take a fingerprint to entirely skeletonized, depending on the circumstances of their burial (time of year, depth, variety of peatland, etc.) as well as preservation efforts undertaken post-exhumation.

The Archäologisches Landesmuseum at Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany displays bog-preserved remains that exist at various points on this spectrum.

General Notes on the Exhibit

It was apparent upon purchasing tickets that the museum considers its notable collection of bog bodies to be one of the main attractions. The cashier, upon handing me the map, circled the rooms where I could visit the bog bodies without my having mentioned any special interest in them.

There are two exhibits relevant to bog-related finds. The majority of the bodies are presented in an exhibit titled Moorleichen: Menschen der Eisenzeit which translates to “Bog Bodies: People of the Iron Age.” Unlike the museums in Denmark, which frequently included versions of the text in Danish, English, and occasionally in German, the labels at the Moorleichen exhibit were in German only. This was not surprising; I got the impression while spending the week in Schleswig-Holstein that it was not as popular of an international tourist destination as some other German states (e.g., Bayern, or city-states like Hamburg).

As far as how this impacted my experience as a museum-goer, my knowledge of German was sufficient enough to understand most of the signage. I did note, however, that my husband (an archeology student who speaks some limited German) had trouble engaging with the displays without my help translating the labels, especially those that were text-heavy. Many of the docents spoke languages other than German and were available to assist visitors and answer questions throughout the museum.

I would describe the exhibit as being somewhat text-heavy. The label for each body includes a few contextual paragraphs, which I will touch on separately. There are additional labels describing the Iron Age as a whole and theories about why these bodies were buried in bogs in the first place.

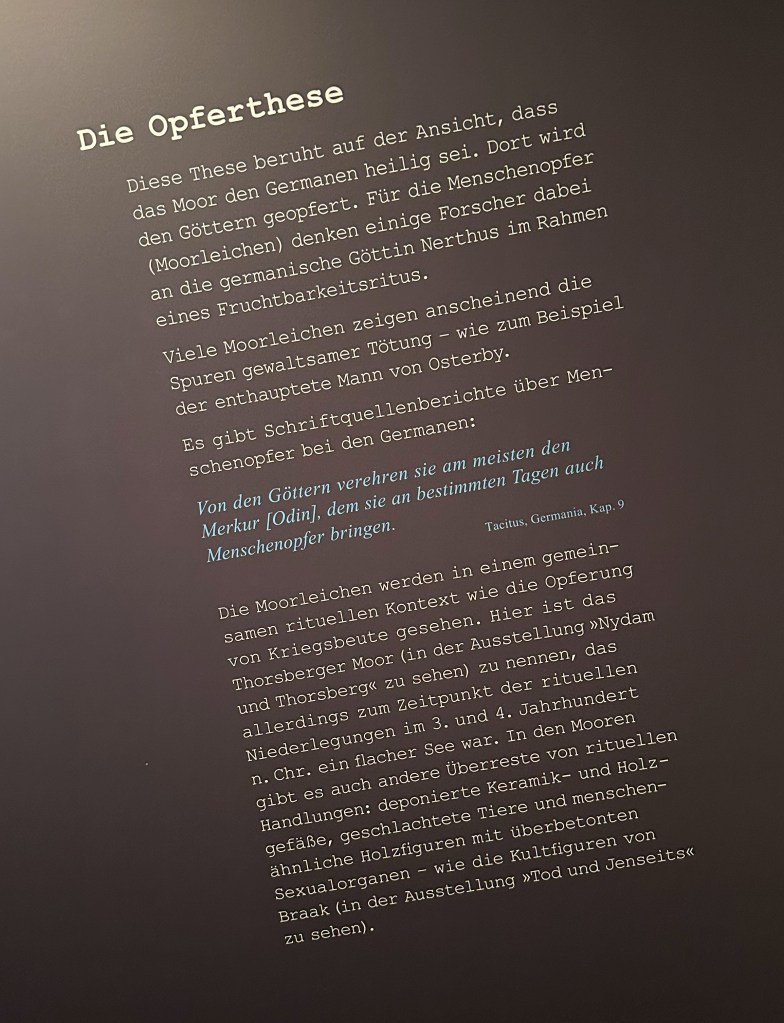

One placard—that which touts the possibility that bog burials were a punishment, as opposed to serving sacrificial or funerary purposes—includes excerpts from Tacitus’ Germania, one of few written sources available to use for studying Iron Age Germanic peoples. This except serves as evidence that men were buried in the bogs as punishement for cowardice. However, Tacitus’ account is generally taken with a grain of salt for a few reasons. As a Roman ethnographer, he was writing from a foreign perspective, and thus his observations would’ve been subject to his own biases. Beyond this, there is no evidence that Tacitus ever visited Germania to make his own observations, which means his work was likely based on whichever second-hand accounts were available to him.

Traitors and deserters are hanged on trees; the coward, the unwarlike, the man stained with abominable vices, is plunged into the mire of the morass, with a hurdle put over him.

Tacitus, GermaniaI’ve included a brief video of the exhibit below to give an idea of how the bog bodies are positioned within the display. As is somewhat standard, the bodies are tucked around a corner to prevent unsuspecting visitors from stumbling upon them, though given the prominent signage identifying the exhibit, it seems unlikely that any German speaker would come across the remains unaware.

Bog Bodies at Schloss Gottorf

The majority of bodies on display at Schloss Gottorf were discovered prior to P.V. Glob’s work with Grauballe Man in 1952, which would ultimately impact the way bog bodies were preserved and displayed. It is obvious that Schloss Gottorf’s displays have been updated fairly recently, but as to ongoing preservation efforts, I had a difficult time finding reliable information.

Due to the sheer amount of information being covered, I have decided to split this into several articles, each focused on a body in Schloss Gottorf’s collection. Below are links to those articles which have already gone live, as well as the names of bodies whose articles I am still working on:

Osterby Head

Rendswühren Man

Dätgen Man

Windeby I & II

Damendorf Man

-

Interning at Orono Bog Boardwalk

Strange as it may sound, one of the perks of moving to New England—for me, anyway—has been easier access to peatlands. I’m originally from Southern California and my previous encounters with bogs had all taken place oversees. A couple months after making the move cross-country, I visited the Orono Bog Boardwalk in Bangor City Forest and was impressed with both how easy it was to find (European bogs, in my experience, are not always easy to track down) and its popularity.

My graduate program required me to complete two internships. Given my interest in peatlands, the Orono Bog Boardwalk seemed like an interesting and relevant internship opportunity. My hope was that I might learn more about the ecology of peatlands by working at the bog. I reached out to the boardwalk director and arranged to work a docent position over the summer.

Docents are stationed in a cabin near the trail entrance, where they are available to take a tally of visitors, document any wildlife sightings, answer questions, accept donations, and sell souvenirs including hats, books, stickers, and T-shirts. Prior to starting my internship, I attended a one day training session on opening, closing, and emergency procedures. Otherwise, it was left up to docents how knowledgeable they made themselves about the bog itself. I focused on educating myself on the ecology of northeastern peatlands.

According to the National Park Service, the Orono Bog was made a National Natural Landmark in 1973 (the marker pictured above was placed in 1974). However, it wasn’t made publicly accessible until 2003 thanks to the installation of a floating boardwalk. The boardwalk comprises an approximately one-mile loop trail with educational signage at various points throughout. It passes through the various stages of wetland, beginning with a raised wooded fen and culminating in the moss lawn of the raised bog, pictured on the map before the start of the trail.

Peatlands are not uncommon in the northeastern United States, but many are inaccessible to the public. Ecology of Peat Bogs of the Glaciated Northeastern United States defines a bogs as “nutrient-poor, acid peatlands with vegetation in which peat mosses (Sphagnum spp.), ericaceous shrubs, and sedges (Cyperaceae) play a prominent role. Conifers, such as black spruce (Picea mariana), white pine (Pinus strobus), and larch (Larix laricina) are often present” [Damman]. Orono Bog is classified as an ombrogenous or raised peatland, with the moss lawn sitting above the groundwater level and sustained by periodic rainfall [“Ombrogenous Bog”]. This is the variety of peatland that typically produces the bog bodies we’re familiar with, but if any such burial practices existed among the indigenous peoples of the northeast, their remains are protected from exhumation by NAGPRA.

The boardwalk cuts through a wooded fen: a younger, more mineral-rich variety of peatland Still, this does not prevent visitors from inquiring about bog bodies. The Bangor City Forest website touches on western European beliefs about bogs and there was one school group visiting Orono over the summer who specifically requested that the tour guide discuss bog bodies with the children. While docenting, I was always excited to answer bog body-related questions. While we may never know whether Orono Bog is the final resting place for any human remains, the same processes have undoubtedly preserved the remains of animals who met an unfotunate end in the bog, and the subject obviously holds a sort of morbid appeal among the public.

Of course, the boardwalk drew visitors with a wide array of interests, including birdwatchers, amateur botanists, tourists, and hikers. It is wheelchair accessible, which is an advantage over more traditional nature trails.

It is interesting to compare the Orono Bog Boardwalk to European bogs like Bjaeldskovdal Peat Bog in Denmark, which I visited in September not long after finishing my internship at Orono. Being that Bjaeldskovdal was previously drained, there is little need for a floating boardwalk to protect the natural flora; however, I would imagine that the resulting dirt path is less accessible. It is worth noting that some better-preserved European bogs do utilize boardwalks, including the Clara Bog in Ireland and the Great Kemeri Bog in Latvia. I felt that Bjaeldskovdal’s site markers for the discovery of the Tollund Man were more engaging than the trail markers at Orono, largely because those at Bjaeldskovdal are multimedia.

-

The Tollund Man and Elling Woman: A Meeting at Silkeborg Museum

As fond as I am of bog bodies in general, I have something as a soft spot for the Tollund Man. Perhaps it’s that his expression is one of the most peaceful, so well-preserved that he almost appears to be sleeping. Perhaps it’s the role that Danish bog bodies (and Danish archeologist P.V. Glob) played in establishing a precedent for their preservation and display in museums. Or perhaps it’s simply that the Tollund Man was the very first bog body I learned about—thanks not to a museum visit, but rather thanks to a poem.

On the surface, I suppose it’s fairly typical to say that my undergrad capstone led me to my thesis topic. But it was not, in my case, a smooth transition. My bachelor’s degree is in English literature and my capstone focused on Beowulf. I was working with both the original Old English text and various translations, which introduced me to Irish poet Seamus Heaney (whose translation of Beowulf is considered one of the more readable, though not the most accurate). Among his beloved work is a poem called “The Tollund Man.”

A few years later, when I started working on this project, I felt strongly that I would need to visit Denmark to see some of the most famous bog bodies in person, Tollund Man included. I was lucky enough to receive departmental funding (my most heartfelt thanks to the Nguyen family) that made the trip possible. I promptly reached out to Ole Nielsen, the director of the Silkeborg Museum where Tollund Man has long been displayed, to arrange a meeting.

image credit to martinwm via Wikimedia Commons I was lucky enough to visit the Silkeborg Museum on a day when it wasn’t open to the public, which allowed plenty of time for conversations and photographs uninterrupted. Nielsen greeted me at the door and invited me to his office, where we talked for an hour over coffee before heading through the back to a separate building, which is almost entirely dedicated to the Tollund Man and bog-related finds.

Discovery & Preservation

During our conversation, Nielsen was kind enough to walk me through the history of the Tollund Man from discovery to present. Much of this information was also included in his display.

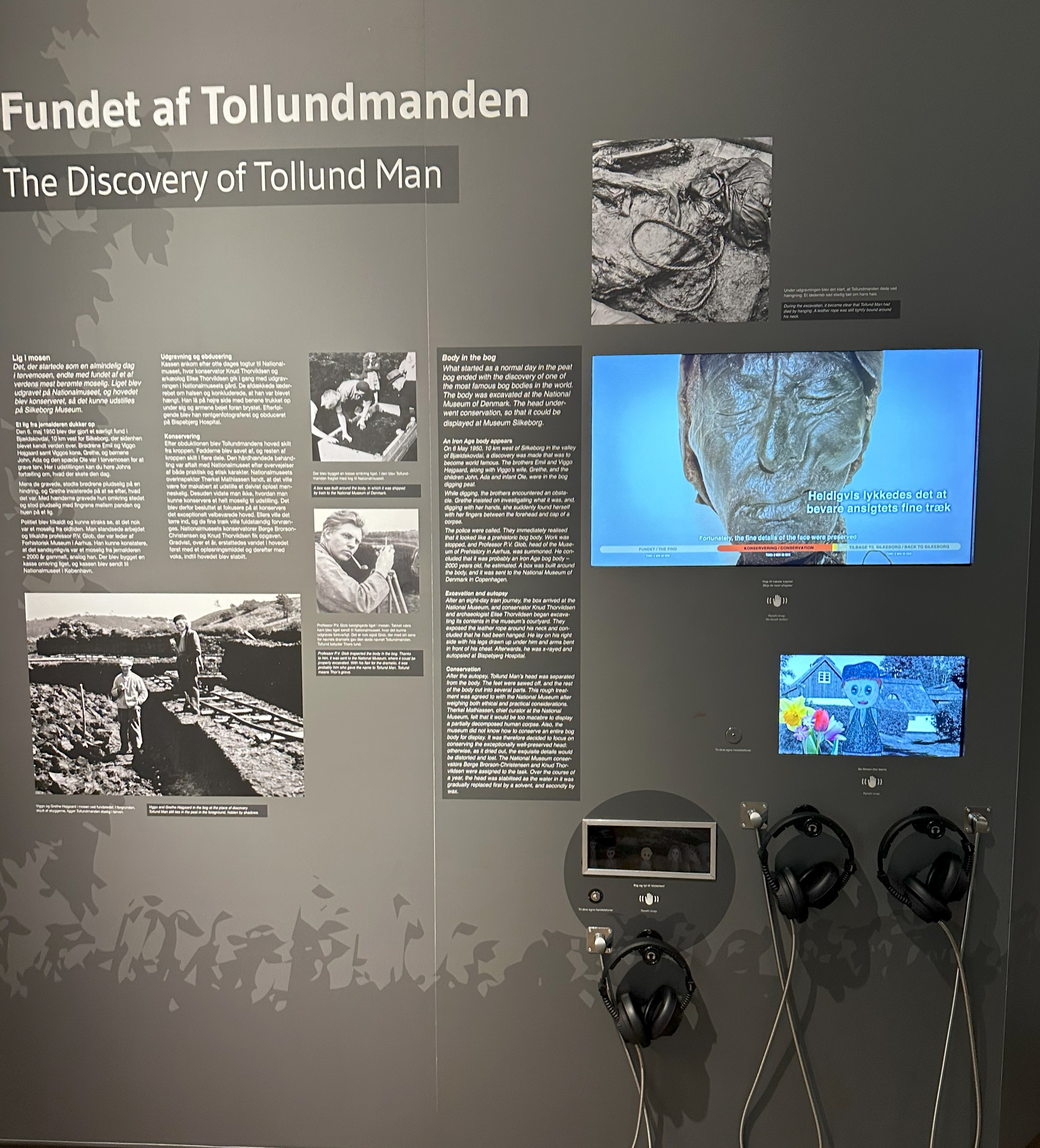

Tollund Man was discovered in Bjældskovdal peat bog near Silkeborg on 8 May 1950 by peat cutters Viggo and Emil Hojgaard. He was not excavated on location, but rather a block of peat containing him was removed from the bog and transported to a different location to allow for excavation under more controlled conditions. Almost immediately afterward, the remains were taken to Bispebjerg Hospital in Copenhagen where an autopsy was performed. This was conducted, presumably, much as an autopsy of a more recent murder victim would be performed. It was established that his internal organs were all present—flattened, but identifiable.

In his digestive tract they found about a quarter of a liter of food, estimated to have been eaten around 12-24 hours before his death. The most current research indicates that this meal likely comprised a porridge of barley, flax, seed, and fish [Nielsen 2021].

There was some hesitation about displaying the Tollund Man at the Silkeborg Museum, initially. This seems on the surface to parallel other debates over whether discoveries should go to state vs. local museums (e.g., movements in England that called for the Lindow Man to be returned to Cheshire rather than displayed in the British Museum), but Nielsen explained that there was in fact little interest on the national level in displaying human remains at the time, with greater emphasis placed on artifacts. In short, there was some question as to whether the Tollund Man would be displayed at all, as this was relatively new ground being tread. Because there were fewer methods available at the time to understand these remains (DNA testing, stable isotope analysis, etc.), researchers at the time did not know what value preserving these remains would hold in the future.

There were, of course, also ethical concerns—was it right to display a human body in a museum? It wasn’t until the Grauballe Man was discovered two years later that archeologist P.V. Glob made the revolutionary decision to advocate for his display in a museum. Glob was also integral in the decision not to excavate the Tollund Man on-site, but rather to transport his remains to another location first.

The method used to preserve Tollund Man had previously been used to preserve fish and tissue for microscopy. This method involves the gradual replacement of water with wax. The head was placed in de-mineralized water to dilute and remove the impurities from the bog water. From there, they added alcohol in increments until eventually the water was replaced with alcohol entirely. The process was then repeated with liquid wax. Afterward, the head was cooled, stabilizing the wax. This process did not merely encase the remains in wax but rather infused them with it, preventing the remains from collapsing on a cellular level.

Compared to the tanning process used to preserve the Grauballe Man, it would appear that this method was more successful in preserving the facial features. though this can also be attributed in part to the exceptional preservation of the Tollund Man’s skull by the bog itself. It is not uncommon for bones to deteriorate or soften under these conditions, resulting in features being crushed beneath the weight of the peat.

The decision was made to preserve only Tollund Man’s head for display. The reasoning behind this is somewhat unclear. It might’ve been due to concerns about the ability to preserve something of this size, given the wax method had only been used on fish and tissue samples before. It might also have felt, in a roundabout way, less shocking to display only a head as opposed to full human remains. Other body parts were preserved for research purposes using alternate methods, but most have not been placed on display.

The Current Exhibit

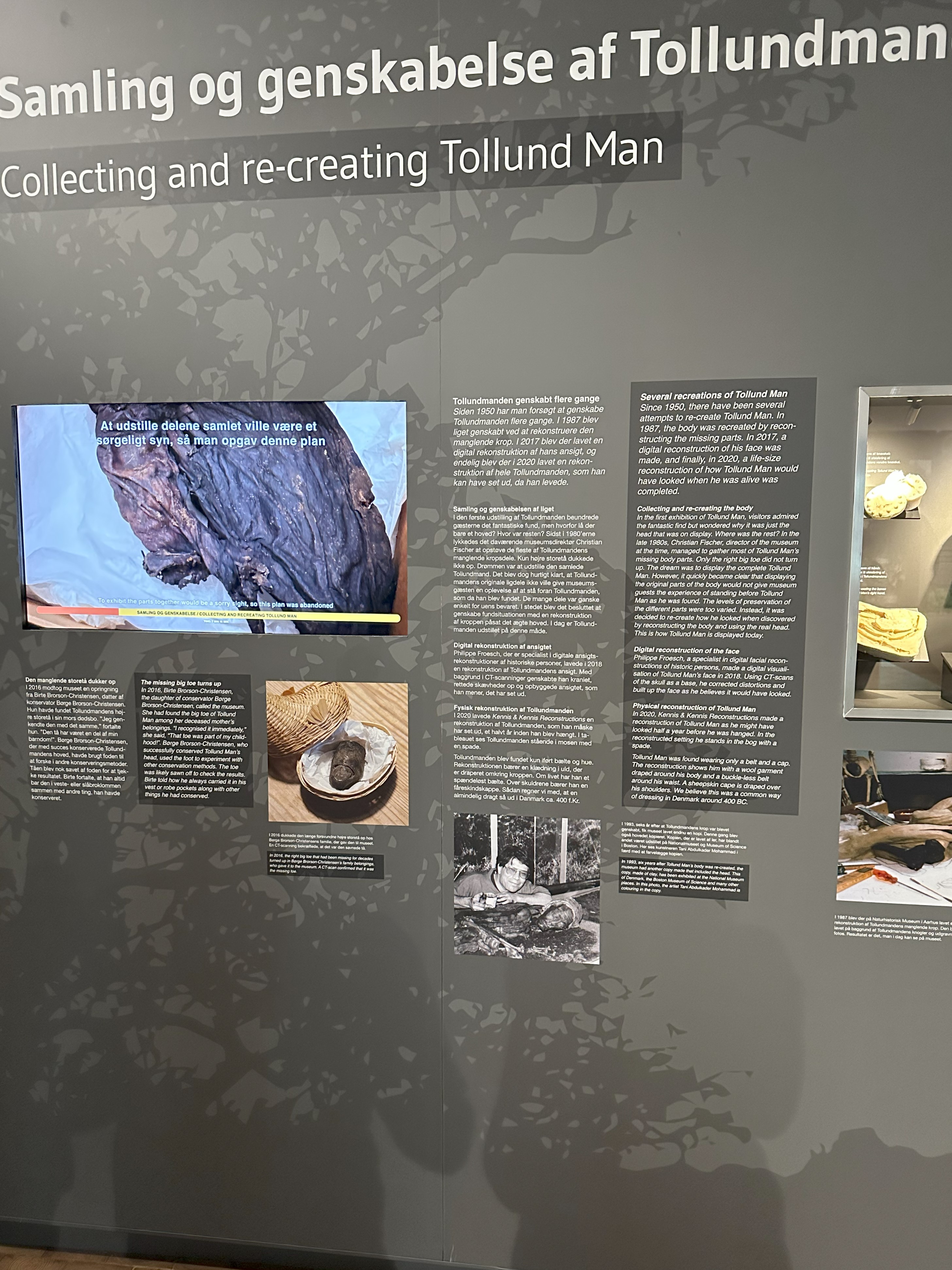

Upon entering the exhibit, visitors are greeted by a reconstruction of the Tollund Man, staged at the center of the room. This reconstruction is the work of Netherlands-based company Kennis & Kennis, who used a 3D scanning and printing to bring the Tollund Man to life.

The effectiveness of facial reconstructions in museum exhibits has on occasion been called into question. Bog bodies are uniquely positioned in that reconstructive artists have more forensic information available to them than, say, if they were working with entirely skeletonized remains. [Wilkinson] In the case of the Tollund Man, it is undoubtedly an accurate reconstructions—any visitor who questions this need only walk a few rooms over and compare the reconstruction against his actual remains.

This, in turn, begs the question: how informative is a reconstruction when much of the same information can be garnered from the remains themselves? More often than not, reconstructions exist to help us humanize the dead, bridging the cognitive gap between a fragmented skull behind a pane of glass and a human life. Bog bodies as well-preserved as Tollund Man are already more than capable of conveying their own humanity—it is for this reason that they have long captured the public imagination.

In the case of the Silkeborg Museum’s reconstruction, they obviously have both the financial means and space to accommodate the reconstruction, so this is by no means a criticism of their display. I simply wanted to take this opportunity to address the necessity of reconstructions in designing bog body exhibits. Many spaces choose to prioritize contextual information and artifacts over reconstructions—for example, the British Museum previously commissioned a facial reconstruction of the Lindow Man, but it was eventually removed from display. Although I have previously criticized the British Museum for its design choices, I believe the decision not to include the facial reconstruction in the current display was the right one, given the already limited space the display designers were working with.

But I digress. The room surrounding the reconstruction is chock-full of information and media that contextualizes the Tollund Man’s discovery, preservation, and subsequent reactions to him over the years. As mentioned in the section above, when the Tollund Man was first discovered, the decision was made to only preserve his head for display. Display cases around this entry room explain this decision in more detail; they also feature body parts that were separately preserved for various reasons, including the right foot and a toe that was taken by a researcher and kept for years (a good luck charm or a keepsake?) before being returned to the museum in 2016.

Text is in both Danish and English. The director himself pointed out the reliance in some places on large paragraphs of text, but this is supplemented by an array of other media, including video and audio components.

East of this first room is a hall which houses the Elling Woman and other bog-related finds. This took me somewhat by surprise, as the Elling Woman is herself a bog body and I had expected her to be treated with similar reverence to the Tollund Man; the director informed me that, given the funding, the museum would choose to upgrade her display, but it sounds as though this is not feasible at present.

Like the Osterby Head displayed at Schloss Gottorf, the Elling Woman is perhaps most noteworthy among bog bodies for the preservation of her distinctive hairstyle. She is otherwise not so well-preserved as the Tollund Man; her face and organs had all deteriorated by the time she was discovered [Gill-Robinson]. She is displayed wrapped in her sheepskin cape and leather cloak on a bed of stepped peat. Beside her, a number of mannequin heads demonstrate how her hairstyle (sometimes called an “Elling Braid”) was achieved.

Other artifacts on display in this hall include bronze neck rings, wooden effigies, and human bones. This room felt a little less interactive than the entrance hall, and there was significantly less context provided for the Elling Woman compared to the Tollund Man. It felt as though this room was dedicated more to explaining the cultural significance of bogs among Bronze and Iron Age peoples as opposed to highlighting any one discovery.

Which leads us to the third and final room. The only object on display in this room is the Tollund Man himself; with the exception of one wall of text, the exhibit relies on the previous rooms to contextualize the Tollund Man for the visitor. The lights in this room are on a motion sensor, meaning the display is kept entirely dark unless someone is visiting [“Seværdighed i Silkeborg”]. Considering other bog bodies like the Lindow Man have suffered light damage due to excess exposure, this seems a sensible precaution [Bradley 2008].

The preserved head is displayed with a reconstructed body, almost identical to early photographs from around the time of his excavation. The case is lit from within, a design choice which prevents the glare/reflection that is so often disruptive in viewing dimly lit displays. Additionally, stools are available for those who wish to sit and contemplate the Tollund Man, and there are handrails surrounding his case, presumably to assist anyone who wishes to lower themselves to get a closer look at his face.

Director Ole Nielsen was also kind enough to let me have a look at the climate controls for the Tollund Man’s case, a system which involves temperature controls and a small tank of distilled water to control humidity levels.

This is a museum that was able to dedicate time, resources, and space to thoroughly contextualizing the bog bodies in its care. Unlike larger museums like the British Museum and the Moesgaard, who are responsible for a wide array of artifacts in addition to any bog bodies in their collections, the Silkeborg has unquestionably presented the Tollund Man as their star attraction.

The Poem

Appropriately, an excerpt of the Seamus Heaney poem is featured in the Silkeborg Museum’s display, written into the guest book by Heaney himself when he visited in 1973:

from The Tollund Man

Bridegroom to the goddess

She tightened her torc on him

And opened her fen,

Those dark juices working

Him to a saint’s kept body . . .

Seamus Heaney, 16th October 1973 -

A Visit to Bjældskovdal Peat Bog

Several years ago now, I had a conversation with a Danish friend about how incredibly difficult it can be to locate peat bogs via modern maps. I wondered if perhaps this was because bogs don’t often rank very high as tourist destinations (some of the bogs here in Maine being an exception), but my friend was quick to point out that many of these wetlands simply don’t exist as they once did. Peat was harvested as a fuel source for thousands of years without significantly impacting the ecology of raised bogs throughout Europe, but technological advancements in the 19th and 20th centuries disrupted this balance. Bogs were methodically drained and the peat harvested in increasingly large quantities, with the drained and harvested land being repurposed for agriculture. Today, over 95% of the raised bogs in Denmark—once covering approximately a quarter of the land mass—have ceased to exist [Stenild 2011].

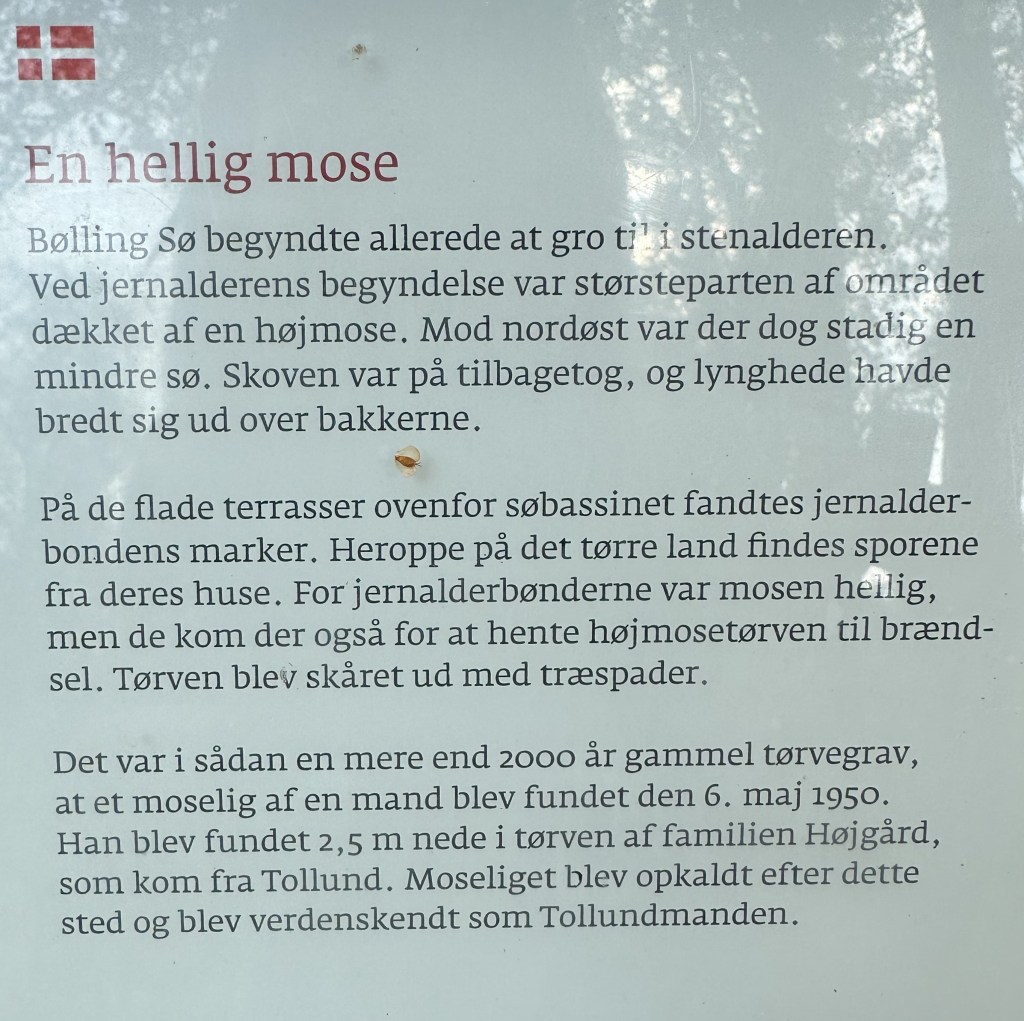

So, when I visited Denmark in September 2023 in order to conduct research for this project, I wasn’t holding my breath that I’d be able to visit the bogs where Tollund Man or Grauballe Man were found. I was pleasantly surprised when director Ole Nielsen at the Silkeborg Museum informed me that there was a nature trail at Bjældskovdal Peat Bog that included signage in the location where Tollund Man was unearthed. The bog, he explained, had in fact been drained and harvested in centuries past, but the Danish Ministry of the Environment had since undertaken efforts to “rewet” the land. Rewetting is not necessarily a restorative process in that the reintroduction of water does not immediately reproduce the conditions which caused peat to form, but it is beneficial in reducing carbon emissions, to which drained bogs contribute significantly [Kreyling 2021].

Bølling Sø (the name of the reconstituted lake) is located about 10km from Silkeborg. The address for the parking lot closest to Tollund Man’s discovery site can be found at Fundervej 71, 7442 Engesvang, Denmark. There is a sign in the parking lot that shows the location on a map.

The hike was easygoing, around 2km (1.2mi) round-trip with little to no elevation gain. Along the way, we took in picturesque views of the reconstituted lake and heather-covered hillsides with grazing sheep. It is possible to make a few wrong turns along the way, as there are some trails that branch off into the woods and nearby farmland, so it doesn’t hurt to take a photo of the map before setting out just to ensure you don’t get lost along the way.

Obviously, accessibility is going to be an issue with most hiking trails. This trail was relatively flat, and given the relatively short distance, it might be possible to access it via wheelchair or other mobility aid. However, it is a gravel trail and therefore subject to natural imperfections (rocks, puddles, etc.) that might hinder accessibility.

The approximate site of the Tollund Man’s discovery is marked by a plaque fixed to a standing log, which details the date of the discovery as well as the names of the peat cutters who discovered him.

There are a few educational activities installed in this location as well as a brief written summary of the bog’s history in English, Danish, and German. I admired the obvious effort that was made to transform this into an educational space without overpowering the landscape.

There was also a wind-up audio component that explained a bit about the Tollund Man and an iron cut-out that showed his silhouette lying in the position he was discovered. I took video of both of these features as well as the surrounding area, embedded below. According to the audio, the precise location of the Tollund Man’s discovery was approximately 50m northeast of the current marker, in a lightly wooded area off the trail. Presumably this was done to minimize interference with the local landscape.

Having not expected to be able to visit Bjældskovdal Peat Bog at all, I was pleasantly surprised by both the ease of access and the attention to detail that went into this location. While it is not a museum display in the traditional sense, the Danish Ministry of Environment took great care installing interactive markers that contextualize the importance of this archeological site through mediums that will appeal to a wide array of visitors.

-

Displaying the Lindow Man: A Case Study

Tucked into a dark corner of Room 50 in the British Museum lies the body of a man who died two thousand years ago. In a hall filled mostly with jewelry and Celtic artwork, he is alarmingly human and well-preserved—the sole glimpse at an Iron Age face in a gallery dedicated to Iron Age Britain and Europe.

My last visit to the British Museum was in December of 2019, roughly six months before I decided that I wanted to pursue my master’s, and long before I settled on bog body displays as the focus of my master’s project. But the visit made enough of an impression on me that I wrote an article about it over on my personal blog. I was fascinated by the Lindow Man but underwhelmed by the manner in which he was displayed. He felt almost like an afterthought—second to the material culture that surrounded him.

The British Museum prides itself on many of the human remains in its possession, including its extensive collection of Egyptian mummies, but at present, the Lindow Man is largely overlooked. He rarely appears in modern marketing materials and, unless they already know he’s there, countless visitors pass through Room 50 without a second glance in his direction.

This was not always the case. Since his sensationalized discovery in 1984, the Lindow Man has been featured in a number of exhibits, each with its own approach to contextualizing his remains. In order to better understand (and, possibly, critique) the present display, there are a number of factors that must be taken into account.

Room 50: Britain and Europe 800 BC–AD 43 at the British Museum The Lindow Man received significant news coverage at the time of his discovery. Public interest in the body was high—after all, he was arguably the most well-preserved bog body found in Britain up to that point, comparable to the Tollund Man and Grauballe Man in Denmark. There was little question as to whether he should be displayed; the issue instead was how he should be displayed, and what sort of treatments were required to ensure he did not deteriorate in the process.

Re-exposure to oxygen causes bog bodies to rapidly decay. For this reason, the Lindow Man was kept in cold storage at a mortuary while British archeologists consulted the specialists who aided in the preservation of the Grauballe Man and Tollund Man. It was agreed that the best option was for the Lindow Man to be freeze-dried [Omar 1989]. While this method was largely successful, there were still a number of potential threats that the preserved body might be susceptible to, including the re-absorption of moisture if his environment was not carefully regulated or infestations by bugs and other pests. Common cautionary measures include a climate-regulated case, allowing for control of the temperature, oxygen, and moisture levels in order to minimize further decay of soft tissue. Light exposure also poses an issue; bog bodies are often displayed in dimly-lit spaces, protected by UV-absorbent films [“Displaying a Bog Body”]. In the case of the Lindow Man, the information on the exact specifications is more readily available than is true of some other bodies, thanks to extensive scholarship on his conservation:

“At [the time in which the Lindow Man was first put on display], a relative humidity (RH) range of 55 + 5% was in common use for organic objects, but because of the considered sensitivity of the object the initial specification for RH was 55 + 2%. Temperature was specified at 19 + 2C and light at 100 lux with no ultraviolet (UV) radiation allowed. Because of the difficulty of achieving this specification, before Lindow Man went on display the RH was widened to 55 + 5%, and the ambient gallery temperature was accepted. Later, in 1989, the specification for light was reduced to 50 lux.”

Bradley 2008It was later decided that the Lindow Man’s display case should include a canopy to further reduce light exposure, suggesting that these initial precautions were insufficient to prevent light damage (in fact, researchers in 2008 observed that the skin had discolored since the initial freeze-drying treatment; the source of the discoloration was not definitively determined, but light exposure was believed to be a possible culprit). According to the British Museum’s online collection, two additional conservation treatments have been performed while the Lindow Man has been in their care: a vacuum-cleaning to remove dust and peat fragments in 1997, and a light cleaning to remove debris a decade later in 2007 [“Bog Body; Arm Band; Garotte,” The British Museum].

All of the aforementioned concerns and practices must be taken into consideration when designing a display for bog-preserved remains. It would seem that the Lindow Man’s current display meets the requirements; as of 2008, researchers concluded that the body was in stable condition, presumably no longer subject to light exposure [Bradley]. While this indicates that the display has succeeded in addressing logistical concerns regarding preservation, its design leaves something to be desired.

As described at the beginning of this article, the Lindow Man is currently presented in a slightly overwhelming hall of Iron Age artifacts, covering quite a broad period. Many of these artifacts are jewelry or artwork, though the Lindow Man is not placed in direct conversation with the material culture of his time. This contrasts the vast majority of other bog body exhibitions, which are often centered around boglands or the bodies themselves. The National Museum of Ireland, for example, holds a number of well-known bog bodies found at Baronstown West, Clonycavan, Gallagh, and Oldcroghan, all of which are housed in a permanent exhibition titled “Kingship and Sacrifice.” This exhibition takes a more speculative approach to presenting the bodies: it posits that human sacrifices and the subsequent depositing of their bodies in bogs was related to kingship rituals during the Iron Age, and contextualizes the entire display around this potential explanation [“Permanent Exhibition: Kingship and Sacrifice”]. The Moesgaard Museum, which is home to the Grauballe Man—perhaps the most famous bog body ever placed on display, thanks to the work of Danish archeologist P.V. Glob—takes a similar approach, presenting visitors with other bog-related finds and a tactile, “peat-like” floor. The Statens Historiska Museum in Stockholm centers its “Prehistories” exhibit around eight life stories, some of which are focused on bodies found in bogs and wetlands, including the Granhammars Man [“Eight Life Stories”]. It is clear from these examples that there are more engaging ways that a bog body could be presented within the context of its exhibit. The Lindow Man is not currently presented as part of any narrative history any more than the pieces of jewelry and artwork are, let alone as a focal point of that history. But when the well-preserved body of an Iron Age man fails to be a focal point in an exhibit about the Iron Age itself, the exhibit is failing to do his remains justice.

The most obvious argument against this is the issue of unsuspecting visitors stumbling upon the Lindow Man. When I sat down with museum director Ole Nielsen at the Silkeborg Museum in September 2023 to discuss preservation and display methods, he speculated that perhaps this concern was an “Anglo-Saxon” one—that not every culture feels the need to shield museum-goers from seeing human remains. My own experiences visiting continental European museums would seem to agree with that assessment. Small, more localized museums (in other words, museums that do not see many international visitors) display human remains in an unabashed manner. Take, for example, the Fehmarn Museum in Burg auf Fehmarn, an island settlement in northern Germany, where Iron Age skeletonized remains are displayed absent any sort of preface or warning, in a case alongside a model ship, beads, and pottery fragments.

If some level of discomfort with human remains is indeed more prevalent in the United Kingdom or the English-speaking world as a whole, it should come as little surprise that the British Museum has relegated the Lindow Man to a quiet corner. This project has little interest in criticizing museums for adhering to cultural sensibilities. Rather, I believe there are more thoughtful ways the Lindow Man could be displayed while also taking these concerns into consideration.

The “Kingship and Sacrifice” exhibit in Ireland features spiral walls that protect visitors from coming face-to-face with the bodies unintentionally while simultaneously placing the bodies at the heart of the exhibit—the spiral shape leads visitors past relevant Iron Age artifacts and other items found in bogs until it culminates in a viewing space for the bodies themselves. A bench is provided from which the bodies can be viewed [“Bog Bodies and Curated Space”]. The Grauballe Man in Denmark is displayed in a room of his own at the bottom of a staircase, where, he can be easily avoided by guests who are uncomfortable viewing human remains, but where he is nevertheless presented within the context of his burial and subsequent discovery. The round room also features seating for those who wish to absorb what they see in what the website refers to as a “quiet and reflective space” [“The Current Exhibition”]. Also in Denmark at the Silkeborg Museum, the Tollund Man is housed in a separate room from the rest of an exhibition dedicated to bog bodies and bog-related artifacts, with lighting that turns on when guests step into the room [“Seværdighed i Silkeborg”]. All of these exhibits feature the dim lighting and climate control needed for proper conservation while also accommodating visitors who are uncomfortable with viewing human remains and would prefer to avoid them entirely.

But why is coming face-to-face with a bog body necessary for communicating these histories at all? First and foremost, the bodies themselves are the only explicit evidence we have for this kind of burial; written sources about Iron Age Germanic and Celtic cultures are primarily Roman and often second-hand accounts, with no attestations of bog burials or sacrifices. Displaying the bodies is therefore the most effective way to convey this history to the public and to provide visual evidence of the unique preservative qualities of peat bogs. Additionally, most curators and archeologists who take an interest in bog bodies seem to agree that a large part of their appeal is in their inherent human-ness—unlike skeletonized remains, many of their distinct features are still apparent, down to fingernails and facial hair. This recognizability breathes life into the past, for the average observer, in a way that artifacts and other types of remains often cannot. Bog bodies have an exceptional and unique capacity to inspire interest in and empathy for ancient peoples.

The Lindow Man himself has been moved around since his discovery in 1984, both within the British Museum and on loan to two other institutions, which means that he has been displayed in more ways than one—and arguably in more thought-provoking ways than his current display. He was originally housed in the now-defunct Archeology in Britain exhibition, which placed him in the context of recent archeological finds rather than in the time in which he lived. He was then loaned out in 1987 to the Manchester Museum before being returned to the British Museum in 1988, after which he was housed in the Central Saloon Galleries, but was subject to too much natural light, so a canopy was added to his case. Here, his position in the gallery was prominent. He was displayed alongside the Hinton St. Mary Mosaic, a 4th-century Roman mosaic found in England. It could be argued that these two items are loosely related, being Archeological finds from Iron and Bronze Age England, but how this was contextualized within the exhibit is unclear.

Jody Joy discusses how bog body displays often give thought to the context of the body’s discovery, because for many bog bodies—as is the case with the Lindow Man—the discovery of the body is as much a part of history as the body itself. In discussing various methods of designing display around bog bodies, he said:

A great deal of emphasis is placed on recreating the context of discovery in the display of bog bodies, creating the impression that they have been freshly exposed and may have ‘died yesterday’ (Giles 2009, 90; Sanders 2009, 220). For example, a cast of the underside of Grauballe Man was created before he was conserved so that they could display him in the exact position he was found in (Glob 1969, 58). Despite the fact that the body of Tollund Man was not originally preserved, they have made a replica of his body for the current display (Fischer 2012, 105–7). An exhibit at the Landesmuseum Natur und Mensch, Oldenburg, Germany, even displayed a bog body behind a huge slice of peat (see Sanders 2009, fig. 6.3). In this instance, the bog body is almost secondary to the natural phenomenon of the peat layers.

Joy 2014Which brings us to one of the more interesting displays constructed for the Lindow Man: his second visit to the Manchester Museum on loan in 2008. In designing the exhibition, the Manchester Museum took a collaborative, community-oriented approach. As a result, “Lindow Man: A Bog Body Mystery” focused more on the Lindow Man’s relationship to the modern English people than it did on any single history. Stories from seven individuals were presented in the exhibit, ranging from the peat digger who found him to a Druid. Rather than Iron Age artifacts, it featured a range of objects like a peat-digging shovel and a pagan wand. The exhibition was controversial, both in academic circles and among visitors. But as Joy notes in his essay, the Manchester Museum’s exhibition generated far more thought-provoking discussion than did the more traditional Iron Age exhibition that followed in Newcastle.

And then, the Lindow Man was returned to the British Museum, where he currently resides in the corner of Room 50 with little to indicate why he is there or his significance to the Iron Age exhibit. His body lies on a bed of dried peat, alongside a photograph of the Lindow Moss where he was found, loosely contextualizing his body’s discovery in 1984. A handful of panels cover some basic questions: What do we know about the Lindow Man? Why did he die? Why did he last so long in the bog?

His current display is functional, but it does not generate interest. It does not present his body with the same respect for the dead as the quiet, contemplative rooms of the Grauballe Man or the Tollund man; it does not emphasize the significance of his discovery or the potential histories in the way the National Museum of Ireland or Statens Historiska Museum’s displays do; it does not challenge us with different perceptions as did the display at the Manchester Museum. Most importantly, it fails to give his humanity a significant role in the exhibit. Room 50 encourages us to admire Iron Age artifacts, but it fails to encourage us to engage with the people who made them. Contrast this with other bog body exhibitions, or with the British Museum’s own Egyptian displays, and it perhaps begins to feel like a missed opportunity.

-

Relevance

The following is adapted from a project proposal submitted as part of an assignment for HIST-890 in the fall of 2022.

The ongoing preservation of northern European bog bodies is first and foremost relevant to the study of Iron Age Germanic and Celtic cultures. These cultures have left behind scant written histories; scholars are largely reliant on archeological evidence, second-hand Greek and Latin accounts or–more removed still–the transcription of presumed oral histories and traditions by Christian monks during the early Middle Ages in order to better understand early Germanic and Celtic peoples [Wells 1990]. European bog bodies are therefore vital to the ongoing study of specific burial practices among early Germanic and Celtic peoples.

The ongoing preservation and display of known bog bodies is especially important when taking into consideration the decreased reliance on fossil fuels and modern efforts to preserve over-harvested peatlands; as less peat is being excavated, there is diminished potential for additional bodies to be discovered moving forward. Even in the areas where peat continues to be regularly excavated (e.g., on various Scottish islands for use by distilleries), the machinery used for excavation risks destroying any remains, and so even at the height of their discovery through the twentieth century, finding in-tact bog bodies was rare [Lobell 2010]. It is therefore both imperative to ongoing research that these remains be, if not displayed, then at least preserved, lest one of the few resources we have for studying these cultures be lost to history.

Compiling preservation efforts and display methods into a blog serves a threefold purpose. First, it makes more transparent the ongoing care and treatment of these remains, which—although preserved for thousands of years by the acidity and often low temperatures in peat bogs—begin to rapidly decay upon re-exposure to oxygen. Early attempts included soaking the remains in solutions and applying protective coatings of either wax or oil, but some of the more recent discoveries—like that of the Lindow Man in the 1980s in northern England—have taken into consideration the successes and failures of preservation methods applied to bodies including Grauballe Man and Tollund Man in Denmark and looked instead to freeze-drying as the preferred method of preservation [Omar 1989]. Further, the initial preservation after removal from the bog is only the first hurdle; ongoing efforts include climate-regulated cases that control oxygen and moisture levels in order to prevent mold or rot, UV-absorbent film to prevent unnecessary light exposure, and pest control [“Displaying a Bog Body”]. Some museums also practice periodic cleaning of the remains, though assuming all instances of these treatments are documented, it would seem they are performed infrequently [“Bog Body; Arm-Band; Garotte”]. Compiling these ongoing concerns, various solutions, and their effectiveness into an online reference helps to establish a standard of care for these remains and, ideally, encourages transparency and accessibility between institutions.

Next, an accessible database opens up the conversation surrounding the design of exhibitions that are both respectful and thought-provoking. Dr. Jody Joy, a former curator for the European Iron Ages collection at the British Museum, wrote on the subject of displaying human remains:

[T]he decision to show human remains should not be made lightly and careful thought must be given to the reasons for and the circumstances of the display. DCMS guidelines stipulate that ‘human remains should only be displayed if the museum believes that it makes a material contribution to a particular interpretation; and that contribution could not be made equally effectively in another way’. Human remains should also be positioned so that people do not come across them ‘unawares’.

Joy 2014Joy goes on to discuss the unique circumstances surrounding the display of bog bodies: the exceptional preservation of skin, hair, and nails offer museumgoers a unique opportunity to look history directly in the face in a way that more deteriorated remains do not, and additionally—whereas the histories of other periods and cultures could in many cases just as well be told through the display of funerary objects and other relevant archeological evidence—in the case of bog bodies, the remains themselves are the most relevant archeological evidence available for the study of this type of burial. For these reasons, the display of bog bodies does indeed make a material contribution to the interpretation that could not be made as effectively through other methods, but the design of their displays is something that should nevertheless be given careful consideration. Well-designed displays should present the remains with a wide array of museumgoers in mind, those who don’t wish to view human remains at all; they should encourage continued public interest in these remains, which in turn helps ensure continued funding and support for the proper care of the remains; and they should function to protect the remains from further deterioration. Many current exhibits do not meet these expectations. Increased transparency would shed light on these shortcomings, perhaps encouraging some museums to reconsider their display methods, and would also provide a reference point for improvements to current exhibits.

Finally, while especially relevant to Iron Age Europe, the conversation surrounding the preservation and display of bog bodies also has implications for the display of human remains on the whole. Bog bodies are Europe’s natural mummies; with the increased likelihood of repatriation in the near future for human remains like the Egyptian mummies currently housed in the British Museum, it might be beneficial to encourage European museums to redirect their focus toward the ongoing care of their own indigenous mummies. Cultivating a renewed public interest in bog-preserved remains and local histories could generate the sort of foot traffic that large institutions fear losing if they repatriate stolen remains and artifacts. Further, making transparent the methodologies for preserving bog bodies could aid in the preservation of other unique organic finds in the future, should their respective countries choose to preserve them. Lastly, information on the design of these exhibitions, including both functional and aesthetic elements, could offer a useful reference point in designing a wide range of culturally sensitive displays.

-

Why Bog Bodies?

The study of human remains, regardless of the context in which they’re being studied, is inevitably viewed as morbid by some of those working outside the relevant fields. Whenever I’m asked about my research interests, one of the most frequent follow-up questions is “why?” While bog bodies have received some attention in recent years thanks to increased accessibility of information via the internet, it is still something of a niche interest, even among museologists. Part of this is due, no doubt, to the seeming lack of practical application: thanks to a decline in the reliance on peat as a fuel source, new discoveries of bog-preserved remains are increasingly rare, and only a handful of museums throughout northern Europe have bog bodies on permanent display.

On a personal level, my interest in bog bodies grew out of undergrad research on the cultural history of pre-Christian Germanic Europe. I happened across a mention of the Osterby Head and went down a research rabbit hole, though there was no way to tie it into the capstone project I was working on at the time. That interest wasn’t cemented until a year and a half after graduation, when a friend invited me to London. While there, I made it a priority to visit the Sutton Hoo helmet at the British Museum. The Lindow Man—a bog body on display in the Iron Age room—was something of a peripheral interest, but I was so struck by the display that I ended up writing an article about the visit over on my personal blog.

Which leads me to the professional relevance of this project: I felt the display was poorly designed, though I didn’t have the knowledge to support this belief at the time; it was more like a gut feeling. The body was tucked into a dimly-lit corner in a very large room, quite easily overlooked, his case indistinguishable from the surrounding cases housing Iron-Age tools, clothes, and jewelry. There was no prominent signage to direct visitors to the body and it plainly did not draw the same attention as other remains housed in the museum (e.g., the multiple rooms displaying Egyptian mummies). On a busy Sunday, I was alone in that particular corner of the British Museum—the Lindow Man’s only visitor.

The visit raised a number of ethical and logistical questions for me. What all had to be taken into consideration when designing this sort of display? How was the body preserved once it had been exhumed from the bog, and did that limit the way curators could design an appropriate space? Was anyone opposed to these displays on a moral basis? Perhaps there was some context I was missing in judging the Lindow Man’s display so harshly.

There are believed to be around 45 bog bodies that remain in-tact today, many of which are displayed in museums [Gill-Robinson 2005]. This blog will look at current and past scholarship on the preservation of said bodies; provide an overview of the numerous challenges and considerations that go into preserving an exhumed bog body and placing it on display; and attempt to determine how successful many of the present displays are in addressing the aforementioned concerns.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.