This post is part of a series on the bog bodies displayed at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum at Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig, Germany. You can read the introductory post here.

A History of the Rendswühren Man

Found in June 1871, the Rendswühren Man marks the oldest date of discovery among the bog bodies in Schloss Gottorf’s collection. P.V. Glob puts the location of his discovery at Rendswühren Fen near Kiel, Germany, though some online sources alternatively refer to this location as “Heidmoor.” According to an article by Angelika Abegg-Wigg (the current curator of Iron Age artifacts at Schloss Gottorf) and Ben Krause-Kyora, the bog in question is additionally sometimes referred to as “Großes Moor”—literally “Big Bog” [Abegg-Wigg 2016]. They place the bog between Neumünster und Bornhöved, south of B430.

The name(s) of whoever discovered the Rendswühren Man (presumably, a peat cutter or cutters) seem to be lost to history. The discovery was investigated by Johanna Mestorf, a self-taught archeologist who is often credited as Germany’s first female professor and who was working as curator of the Kiel Museum at the time.

The exact position of the body at the time of discovery is well-documented: the Rendswühren Man lay face down in the bog at a slight incline with his right foot crossed over his left [Gill-Robinson, who wrote additional articles under the name Gill-Frerking; sources are cited based on the name they were published under], and was naked except for the left leg, which was covered by a piece of leather with the pelt facing inward, and bound by a sort of leather garter. His head was covered in a large rectangular woollen cloth and a cape made of pieces of skin sewn together, with a hole in the forehead, possibly indicating he was struck in the head after being covered [Glob; Abegg-Wigg 2016]. Glob’s wording is somewhat vague, but Abegg-Wigg and Krause-Kyora variously describe the materials used as twill wool (“geköpertem Wollstoff”), sheepskin (“Schaffell”) and leather with hair (“behaartem Leder”). Additionally, a vest and tunic were found near the body [Gill-Robinson]. Early attempts to date the body were based on these articles of clothing, estimated to have been from around 100-200 CE. Over a century later, 14C-AMS dating would agree with this assessment [van der Plicht].

Much of this clothing has deteriorated or been lost. This is due in part to the body being displayed on a farm cart in a nearby barn shortly after its discovery [Glob]. The find was reported in a local newspaper, drawing visitors who took scraps of fabric and other keepsakes before the body was transported to Kiel.

An 1871 journal publication, re-discovered by Heather Gill-Robinson while searching archival materials, documents the discovery, excavation, and examination of the body. Physical examination and autopsy was conducted by a Dr. Hansen and Dr. Kaestner. The skin was described as dark black-brown and parchment-like prior to post-excavation conservation treatments. During the excavation process, the mandible was detached from the skull. The left metatarsals and phalanges were absent, possibly due to damage by the peat spade. The brain was reportedly preserved as a sample for an anatomical museum, but its ultimate fate is unknown [Gill-Robinson].

The body was preserved via smoking in an oven, though records on the specifics of this treatment are limited. Digital radiographs taken of the Rendswühren Man’s head revealed that the skull is missing, having been reconstructed using “wire and several unknown materials.” Gill-Frerking speculates that modeling clay or similar might’ve been used to provide facial structure. Metal rods inserted into the neck seem to have given it an unnaturally elongated appearance [Gill-Robinson; Gill-Frerking]. Another unknown material was used to replicate teeth. The reliance on metal interfered with imaging, and the absence of the skull has made it impossible to compare modern findings against the 19th-century autopsy report [Gill-Frerking].

What’s interesting about the Rendswühren Man is that he was preserved at all—a large number of bog bodies found throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were either reburied or allowed to decay [Joy 2014]. Prior to the Grauballe Man’s discovery in 1952, it was still widely considered unethical to display human remains in a museum [“Displaying a Bog Body”]. Yet Johanna Mestorf and others made the decision to preserve the Rendswühren Man all the way back in 1871. He was left out on a cart for visitors to view—to his detriment, yes, but this nevertheless demonstrates that not everyone had qualms about viewing human remains.

The Present Display

The Rendswühren Man is displayed in a semi-dark room as part of the Moorleichen exhibit at Schloss Gottorf, which is contextualized by various Iron Age artifacts. I have mentioned in previous articles that I am not overly fond of the decision to display bog bodies alongside unrelated Iron Age artifacts—while it places them in the broader context of their era, I’ve found exhibits focused on the cultural significance of bogs and bog-related finds to be more thematically cohesive and engaging.

The State Museum of Archeology is housed in a historic castle, the ongoing preservation of which no doubt presents some limitations as far as space, architecture, and alterations. However, the castle houses a separate exhibit—which I hope to address in a future article—that is more focused on the sacrificial significance of bogs. At present, I am not totally clear on why these two exhibits are separated.

Like the other bog bodies featured in the Moorleichen exhibit, the Rendswühren Man is displayed in an enclosed case with only one glass side for viewing. The backdrop features a sepia interpretation of a shrubby bog and he is presented on a bed of dried turf, lying face up rather than face down as he was discovered. While generally appreciating displays that make an effort to show the body in the context of its discovery, I do think that presenting the Rendswühren Man face up is the logical choice. A rough orange-brown cloth (not believed to be historical in origin) is draped across his pelvis. He was previously displayed without a cloth covering his genitalia; presumably this was changed with the variable sensitivities of museum-goers in mind.

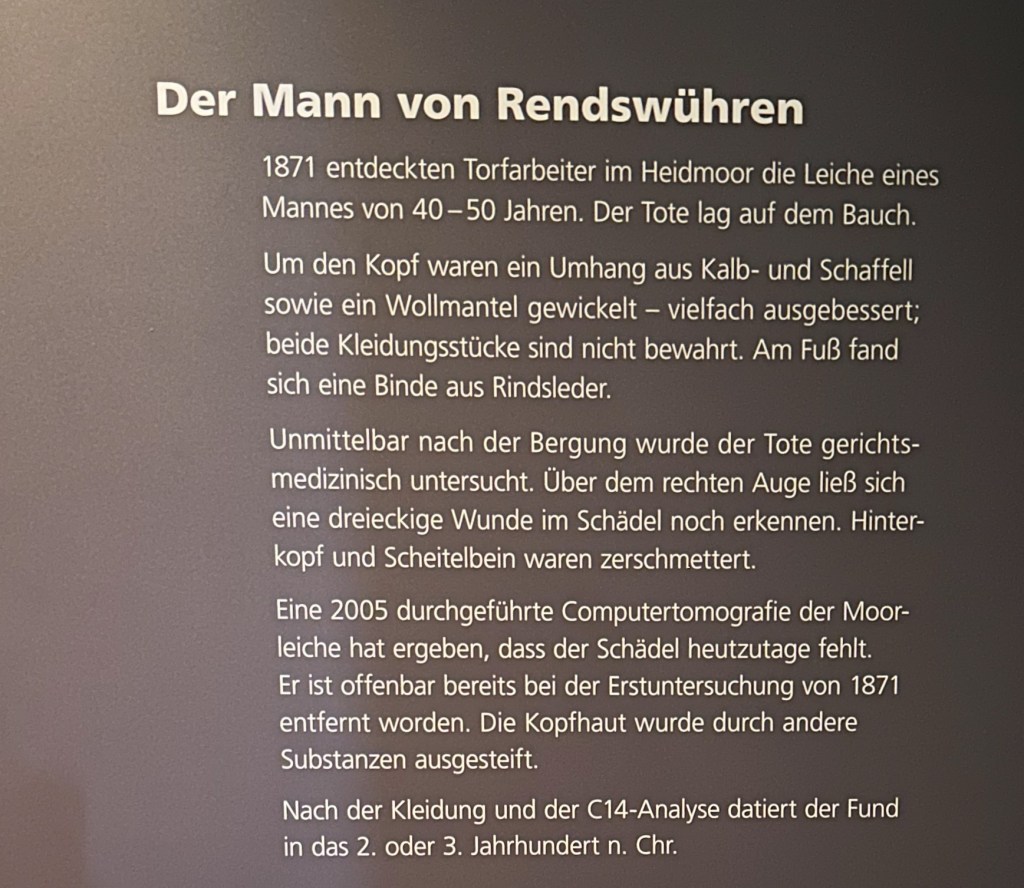

The label for the Rendswühren Man (or “Der Mann von Rendswühren”) describes him as having been approximately 40-50 years of age at the time of death. The cloaks are here described as being made of calfskin and sheepskin (“Kalb- und Schaffell”) as well as wool (“Wollmantel”), with a bandage of cowhide (“Rinsleder”) around the foot.

The label describes an autopsy having been performed on the Rendswühren Man shortly after his discovery; the triangular wound to the skull, also described by Glob, was observed. The back of the skull and parietal bone were also shattered. A tomographic scan conducted in 2005 revealed that the skull was not present, indicating that it was likely removed during the initial autopsy (described in greater detail in the section above; this is the only context the placard provides).

I found it interesting—and a little frustrating—that the Moorleichen exhibit does not seem to mention Johanna Mestorf. The NOVA website cites her as having coined the term “Moorleichen,” and the decision to smoke the body for preservation was undoubtedly revolutionary at the time. Is it necessary to mention relevant archeologists in a museum exhibit, which should perhaps be focused on the finds themselves? I’m not sure where I stand on this. Danish bog body exhibits like that at the Silkeborg Museum certainly do not hesitate to credit P.V. Glob for his contributions to the field, so it feels like the Rendswühren Man’s display is missing context by comparison.

Leave a comment